Hey. It’s me, Catherine Sinow. If you read this magazine, you might recognize my name, as this is my 19th Cipher article (and probably last, since I’m graduating on December 17th). So I figured I have the right to do something that Cipher’s militant editing team would otherwise totally shut down: tell a highly irrelevant personal anecdote about something that happened four years ago.

I need to start by saying that my college counselor pitched college to me as the most utopian place in the known universe. In his vision, every college student is joyful, social, involved, and studious at all times. Oh—and diverse. Don’t forget the diversity. His words: “If you are a black lesbian amputee, you can go hang out with other black lesbian amputees—at the wonderful place known as College!™”

So I applied and got into Colorado College, packed my bags and went. But by the time I finished my first block, things had pretty much gone to hell. My experiences ranged from dull to terrifying. I was in the middle of a mind-numbing beginning Spanish FYE, during which I went to the Baca campus and got food poisoning and had to listen to my classmates tell rape jokes. Back at campus, a peeping tom snuck into Loomis and took over-the-stall pics of girls showering—in the very bathroom I used regularly. He went to prison. And then this happened:

Friday night of my first block break, I decided to celebrate the completion of my very first block. I had made one decent friend so far: my hallmate Tiffany (fake name), a soft-spoken physics major who lived in a highly organized dorm room with someone else named Tiffany (fake name, but they had the same name). We ate dinner downtown at the Melting Pot, where I learned that mediocrity and luxury can and do coexist. We sat in a tiny couple’s booth and boiled our own meat skewers in the pots glued to the table. We were both paleo at the time (the last I heard, she continues to be paleo), so we skipped the chocolate fondue. The waiter was awkward-cute and had a tattoo sleeve. He snapped our picture before we departed (see below).

Tiffany and I were a little afraid of walking home downtown after midnight, but our fears were soothed when we saw how bustling Tejon Street was. It was so bustling that, as I remember it, we strutted down the street in our high heels. But in reality, we were only wearing sneakers.

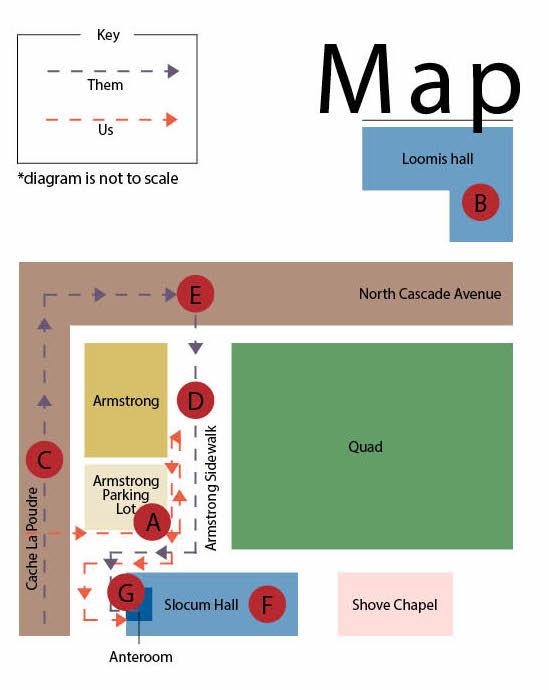

Campus was dark and empty when we got back. At this point, things get a little complicated logistically, so please refer to the diagram. We entered campus via the Armstrong parking lot (A), with plans to walk back to our dorm, Loomis (B). All of a sudden, a grey compact SUV pulled up behind us on Cache La Poudre Street (C). Two chubby dudes in their 30s or 40s sat in the front seat, windows rolled down. The driver yelled at us in a sleazy voice:

“Hey ladies! You want a ride somewhere, or you just gonna walk home?” I deduced that this was a standard catcaller, probably typical of Colorado Springs.

“No,” stammered Tiffany, the more timid of the two of us. But I, fresh out of a crazy gap year in which I had to flee from stalkers in Ecuadorian marketplaces, was feeling a little more aggressive.

“Fuck off!” I yelled.

They drove away. On edge, Tiffany and I continued our walk to Loomis. “Don’t worry. I’ve got my pepper spray and mountain safety whistle,” said Tiffany. She was a very prepared individual.

We began to walk along the Armstrong sidewalk (D) toward Loomis (B), nervous but still pretty confident that we would get home alive. Within a minute, though, we spotted a car creeping down Cascade (E), its headlights like two cat eyes.

“Is that…them?” she said.

“No, that would be ridiculous,” I said. But five seconds later, we realized the cold, savage truth: “It’s them.”

Suddenly, the car turned up onto the curb and zoomed down the Armstrong sidewalk (D), straight toward us. Tiffany screamed, “Run to Slocum (F)!” So we ran. It felt slow and surreal, like trying to run through water. I learned what an adrenaline surge felt like in that moment, but after ten seconds I learned that it can only get you so far, since my lungs were getting parched fast. Maybe my body wasn’t fully convinced that this was life-threatening, and it was saving the ultimate adrenaline experience for running into a mountain lion while camping (this has not yet happened, as I hate camping).

As we were running for our lives, Tiffany started blowing on her mountain whistle. This was not your ordinary safety whistle that people get in handouts during student orientation. It was about as loud as a fire alarm. All over Slocum, darkened windows flicked into brightness and we glimpsed confused residents in their underwear.

After 30 seconds of running (it felt way longer), we finally burst into the Slocum anteroom (G). I turned around and saw the two men from the car rush toward the anteroom from outside. And that’s when it became clear. They had little radios on their pockets. Their beige-collared shirts had patches that read “Campus Safety.” The guys chasing us in a car were actually Campus Safety the entire time.

Now here’s the tricky part. Tiffany and I, being new to the school, didn’t know that a Loomis resident couldn’t swipe into Slocum after 10pm. As I was realizing the true identities of the men who had been chasing us, Tiffany, who hadn’t yet turned around to see who they were, was desperately trying and failing to swipe her card against the sensor box.

One of the guys was short and pudgy with brown stubble. I don’t remember what the other one looked like. Pudgy opened his mouth and said this sentence:

“My name is Richard Newman [fake name], and you don’t tell me to fuck off!”

“Dude,” I said. “We literally thought you were rapists.” Tiffany hid behind me, just now realizing it had been Campus Safety the entire time.

“You don’t belong here!” he spat back. “I knew when you said ‘fuck off’ that you weren’t CC students!”

I took my Gold Card out of my pocket and stuck it in his face. “I literally go here,” I said.

Before she had realized that it was Campus Safety, Tiffany had called 911. I grabbed her wrist and tugged it a bit to encourage her to walk back home with me. She followed me, phone still to her ear. I have no clue where the officers went. I think they probably just hung out in the anteroom and talked about how stupid millennials yell “fuck off” to mighty superiors like Richard Newman.

Tiffany and I walked into the night, past the parked SUV that had just made us run for our lives (I). It was only then I could see the dim, forest green letters printed on the side of the car: “Campus Safety.” I twitched my eyebrows. We went back to Loomis (B) and went to bed in our respective rooms.

The next morning I woke up to a phone call from then-head of Campus Safety, Oliver Holt (fake name), who I later found out had also called my mom. That’s how serious it was. I have no clue how he found out about the incident. Oliver wanted to meet with me ASAP.

He apologized, but it was clear that he was just trying to do damage control. Oliver made excuses for Richard Newman, claiming that he was just trying to be friendly (he did admit that Richard Newman had failed at this endeavor). He also promised that everyone was about to undergo excellent staff training. I suggested that they change the color of the Campus Safety car so that people could actually see that it was the Campus Safety car. They finally did this about three years later.

The next week, I got a follow-up email from Oliver Holt. An excerpt:

“We also called a mandatory meeting with all Safety staff last Thursday morning to discuss a number of issues related to making sure that our focus remains at all times on the welfare of our students, on providing excellent customer service, on the importance of language in our interactions with others, and the importance of making good decisions…although we did not discuss your incident in particular, we spent quite a bit of time talking about what good customer service looks like.”

This didn’t do much to assure me; the damage was done. I only realized how destroyed my relationship with Campus Safety was three years later, at a dorm hall meeting. My RA asked everyone if they had Campus Safety in their phones; I was the only one in the room who didn’t. Whenever people mention “Campus Safety,” I only hear “Campus Danger.”

So yes. This happened. To an innocent freshman, here at the luxurious institution known as Colorado College. Richard Newman got demoted and had to ride a bike. Neither he, nor Oliver Holt, work here anymore.

The thing is, I don’t mean to diss Campus Safety. I’m sure they’ve done a lot of great things for people over the years (although I have no clue what these things are, since I never used Campus Safety’s services due to my aforementioned incident).

What I’m really saying is: no, college isn’t the diverse, studious, blissful knowledge utopia that my college counselor sold me on. But he was right about one thing: college is eventful. Though I may have not experienced the “hall bowling” he described (I forget what he said it was, but I think it involved using humans as bowling balls), I have experienced a lot of chaotic events. There was the time a friend and I bought “gas and bloating relief tea” at Mountain Mama and snuck packets into the tea box in Rastall throughout an entire semester. There was the time another friend and I broadcasted our SOCC show through a fire drill, not even bothering to plug our ears. And then there was the time that my coworkers hacked into a suspicious email account and tried to frame me for sending weird emails because the account had Google searched the name of my high school. (It’s a long story—you can email me for the whole thing.) And of course, there was that time that Campus Safety made me run for my life.

I don’t regret any of this. I’ve come to love it. College may not be the wonderland I was promised, but I think chaos is the next best thing. Now, though, I must say goodbye to this strange life. I will soon leave CC and walk into the horizon of adulthood, a sterile purgatory where everyone works at a desk and has to remember to take out their trash in the evening. Or so I’m told.