Art by Jules Oliff

DIY - Letter From the Editor

Dear Reader,

There is a reason why students at Colorado College love smothering their laptops and water bottles in stickers, knitting their own scarves, and brewing their own kombucha. It’s also why homemade cookies are always better, why handwritten letters hold more meaning, and why you can’t seem to let go of that mediocre paint-by-numbers you did in middle school. Doing something yourself makes it special. Because in a world where everyone is trying so hard to be different while somehow simultaneously being exactly the same, at least I can snuggle up in the blanket I wove for myself (see this issue’s covers) and feel some sense of comfort. No overpriced, pre-distressed jeans and flower-crown-wearing “hippie” or #vanlife poser can take that from me. That’s why I, a replacement art editor who was never officially hired for this job, put my foot down and fought for this theme when no one else did. Somehow, it worked.

Unfortunately, I’m not particularly good at telling stories with words. (I prefer slapping paint around on a canvas.) Lucky for you, the magazine you’re holding is full of stories like mine but much larger, much stronger, and much sexier. Callie Zucker’s piece on masturbation and the pleasure gap (pg. 12) is one of them. Nathan Makela’s interview of an anti-capitalist curator who challenges societal norms with her collaborative projects (pg. 16) is another. I urge you to find love in the dying genre of “prog rock,” as Mira Fisher did (pg. 8), or go a step further and join a DIY art troupe like Kat Snoddy did (pg. 28). And if the stories don’t convince you, let Jules Olliff’s weaving of unconventional materials (pg. 26) and Alyssa Miller’s prints (inside covers and pg. 38) show you what you’re missing in life.

My favorite part about this job I somehow got roped into is that I ended up falling in love with *drumroll*—the people. Who would’ve thunk that a group of idiosyncratic, story-hunting, dry joke-telling, surprisingly sentimental, pajama-wearing grammar nerds could be so much fun to work with? Seriously though, there is debatably no classroom in which I have learned more important values than I have in CC’s publication house. Part of that is because we try to incorporate the collaborative, self-empowering practices of DIY culture into our work process.

This is the last issue that we will be publishing in 2017, but more importantly, this also marks the last issue of our very own Catherine Sinow’s Cipher career. In her time here, Catherine has been an integral part of this magazine’s development as both a contributor and a staff member. She wrote her first article for Cipher four years ago. Eighteen articles later, she bids us a bittersweet farewell in her last Cipher story ever (pg. 44). A strong, zine-making, overall-dress-wearing, passionate enameler, I consider Catherine to be one of the most “DIY” people I know. If you have the chance, I highly recommend that you revisit some of her stories that she wrote throughout the past few years.

So that’s my letter from the editor (or “lettitor,” as I like to call it). It’s not particularly witty or profound, but when supplemented with the work of this issue’s contributors, it might provide a better understanding of what we’re trying to do at Cipher.

In a world where Spotify tells us what to listen to, Instagram tells us what to wear, and Facebook events tell us what to do, having full autonomy over something is a rarity. So, grab a warm beverage, find a quiet spot devoid of consumerist propaganda, and let us show you the importance of doing something yourself every once in a while.

It's been a pleasure,

Caroline Li and the Cipher Editors

An Art of Crisis

Sitting on the Canal St. Martin lends itself to a kind of loitering that only takes place in the public eye of Paris, where the noun flâneur—meaning “lounger” or “idler”—comes to life. It’s summer, and I have reading to do for my class, so I pick a not-so-grimy bit of concrete along the canal and settle into my book. A man approaches me, speaking French. It’s clear that he is trying to sell me something. I politely listen, picking up words here and there, trying not to make it terribly obvious that I’m an American tourist.

He struggles to express what he is selling, so I eventually cave and speak in English. We fumble in English before a friend begins translating in Spanish, and we awkwardly navigate the three languages. Wary of being pick-pocketed, I draw my tote bag nearer to me.

He pulls out a book and my concerns begin to dissipate. My interest now outweighs any concerns about pickpocketing—I’ve devoted most of my free time to making books and studying their history.

His book is a collection of poetry, written in Spanish. It is printed on recycled paper, bound in a cardboard cover that was collaged by hand and sewn with (probably recycled) string. Books like these are called cartoneras, and they are DIY in every sense of the word.

The word cartonera refers both to the books themselves and to the larger movement of cartonera publishers and their nontraditional publishing houses. The movement began in Argentina in 2003, following the 2001 Argentine economic crisis, when the peso’s value plummeted by two-thirds. Within a week, the unemployed population quadrupled. People seeking income began searching the streets for cardboard to resell to recycling plants. These people became known as cartoneros—the term comes from cartón, the Spanish word for cardboard.

By purchasing cardboard from cartoneros, cartonera publishing houses provided economic opportunity in a time of dire economic instability. But more than this, they took book production out of the commercial publishing industry and into the streets. Most cartonera publishing consists of informal workshops made up of editors, cardboard collectors, local artists, and volunteers from the community, all working together to fold pages, paint covers, and bind books.

As the cartonera movement has spread across Latin America, it has adapted to the varying circumstances of each region’s market and population. A few components tend to remain the same: the use of cardboard as cover material, digitally printed writing and photos, and community publishing workshops. But the formula for cartonera publishing is constantly evolving. Sometimes, as in the case of Julio, the same person completes the whole process: making the cover, writing the book, and selling it on the street.

When I met Julio, he had just moved to Paris, and was living near Republique, a politically active neighborhood fitting for a cartonera publisher. He had recently published a second printing of his latest cartonera, “la nouvelle poésie.” Not all cartoneras are filled with poetry, as Julio’s are. Some are photobooks, others cookbooks, and many are also made for children.

After fumbling through French and back to English again, Julio and I eventually exchanged information, and would meet a few times afterwards to continue discussing cartoneras. The last time we talked, he brought several cartoneras to show me—even gifting me a copy of “la nouvelle poésie.” My copy is number 42. To date, Julio has printed over 700 copies, each handbound, each cover hand-designed.

Julio is from Uruguay, but travels between France and Spain to share his cartoneras and promote DIY book-making communities—while cartoneras are pervasive in South American countries, only a handful of cartonera publishers live in Europe. Before France, Julio lived in Argentina, the hub of cartonera publishing. He first learned about cartoneras at the “Feria del Libro de Buenos Aires” (“Buenos Aires Book Fair”), which began in 2011, the same year Argentina was named UNESCO World Book Capital. At that time, Julio’s poetry was being published by an independent publisher, which publishes industrially printed books that are often only sold at book fairs.

Although Julio had already found success in commercially publishing his poetry, he was drawn to cartoneras for the freedom they provided. Cartoneras work without the copyrights on which traditional commercial publishers depend—they’re often called “copyleft.” So they give self-publishers like Julio a chance to break the publishing rules to which they would ordinarily be bound. The cartonera is, in effect, not owned by anyone; it belongs to the community. The liberty of publishing without license grants anyone the ability to be a publisher.

Since cartoneras circumvent the traditional publishing scene, they grant access to literature—a leisure normally reserved for the educated elite—to people who ordinarily do not have the time or money to read. This is how the cartonera has become a democratizing agent for social and political change. Because the books cater to the specific communities they are made in (often lower-class) and made with the help of that community, they close the gap between creator and consumer. However, despite its remarkable adaptability, the cartonera’s ability to enact social change has varied by region.

It was highly successful in Peru, taking a more direct and community-based approach than the Peruvian government had. According to the Peruvian Book Chamber, Peruvians read an average of only one book per year. The Peruvian Law of Book Democratization and Promotion of Reading attempts to improve literacy by expanding the market availability of books. At Sarita Cartonera, a publishing house fittingly named after the Peruvian patron saint of outcasts, the publishers teach the cartoneras supplying the cardboard how to read. The cartoneras are also trained in binding and painting the books, giving them a more prominent and active role in the process of book-making.

The collaborative nature of cartonera-making encouraged Julio to write a new kind of poetry: his first cartonera was filled with collaborative poems, adapted from a game in which one person writes a few words and then another person writes a few words, and together they stumble on something like poetry.

Julio moved to France last spring after the changing political climate in Argentina compelled him to leave. These days, he spends his time publishing work for his editorial group, Sin Licencia, meaning, “without a license.” He makes between 30 and 100 book copies at a time during weekend workshops, selling them with his friends at poetry readings in cafes.

When he isn’t sharing cartoneras on the streets of Paris, he’s organizing gatherings reminiscent of early French Salons. He and a few friends meet at Parisian bistros, where they talk and write over coffee or beer. These gatherings generate content for future cartonera workshops.

While listening to Julio’s story, I found myself wondering how effective the cartonera, an “art of crisis,” born of the economic instability in Latin America, could be in Paris. In places like Argentina and Peru, it was a powerful tool for improving literacy and giving social agency to the poor. Here, as physically beautiful as the book was, it was difficult to see Julio’s cartonera as much more than a recycled cardboard book. What place could cartoneras have as agents of social change in Europe?

Julio believes that no matter where it travels, the cartonera brings a much-needed sense of material connection to readers. He complains of a lack of diversity, color, and personality in the book covers in Europe, saying that they have a “plastic appearance,” not even featuring relevant cover art. Julio is confident that handmade books provide a sense of ownership that is often lost as a result of mass production.

Hearing this, I was brought back to the day Julio first handed me a copy of “la nouvelle poésie,” fashioned from cardboard and printer paper. Even without the context of crisis, or a sense of need for the book, holding an intentionally crafted object made of humble materials challenged my own assumptions about bookmaking. I had always assumed that the most beautiful books would have to be made with the finest, most expensive materials available. But there I was, looking at a little strung-together thing made of cardboard, thinking it was one of the more beautiful, carefully crafted books I’d ever seen.

"I literally go here"

Hey. It’s me, Catherine Sinow. If you read this magazine, you might recognize my name, as this is my 19th Cipher article (and probably last, since I’m graduating on December 17th). So I figured I have the right to do something that Cipher’s militant editing team would otherwise totally shut down: tell a highly irrelevant personal anecdote about something that happened four years ago.

I need to start by saying that my college counselor pitched college to me as the most utopian place in the known universe. In his vision, every college student is joyful, social, involved, and studious at all times. Oh—and diverse. Don’t forget the diversity. His words: “If you are a black lesbian amputee, you can go hang out with other black lesbian amputees—at the wonderful place known as College!™”

So I applied and got into Colorado College, packed my bags and went. But by the time I finished my first block, things had pretty much gone to hell. My experiences ranged from dull to terrifying. I was in the middle of a mind-numbing beginning Spanish FYE, during which I went to the Baca campus and got food poisoning and had to listen to my classmates tell rape jokes. Back at campus, a peeping tom snuck into Loomis and took over-the-stall pics of girls showering—in the very bathroom I used regularly. He went to prison. And then this happened:

Friday night of my first block break, I decided to celebrate the completion of my very first block. I had made one decent friend so far: my hallmate Tiffany (fake name), a soft-spoken physics major who lived in a highly organized dorm room with someone else named Tiffany (fake name, but they had the same name). We ate dinner downtown at the Melting Pot, where I learned that mediocrity and luxury can and do coexist. We sat in a tiny couple’s booth and boiled our own meat skewers in the pots glued to the table. We were both paleo at the time (the last I heard, she continues to be paleo), so we skipped the chocolate fondue. The waiter was awkward-cute and had a tattoo sleeve. He snapped our picture before we departed (see below).

Tiffany and I were a little afraid of walking home downtown after midnight, but our fears were soothed when we saw how bustling Tejon Street was. It was so bustling that, as I remember it, we strutted down the street in our high heels. But in reality, we were only wearing sneakers.

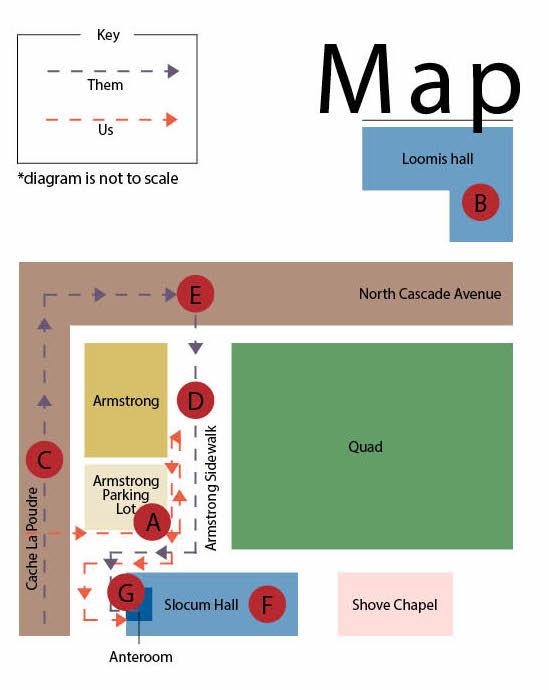

Campus was dark and empty when we got back. At this point, things get a little complicated logistically, so please refer to the diagram. We entered campus via the Armstrong parking lot (A), with plans to walk back to our dorm, Loomis (B). All of a sudden, a grey compact SUV pulled up behind us on Cache La Poudre Street (C). Two chubby dudes in their 30s or 40s sat in the front seat, windows rolled down. The driver yelled at us in a sleazy voice:

“Hey ladies! You want a ride somewhere, or you just gonna walk home?” I deduced that this was a standard catcaller, probably typical of Colorado Springs.

“No,” stammered Tiffany, the more timid of the two of us. But I, fresh out of a crazy gap year in which I had to flee from stalkers in Ecuadorian marketplaces, was feeling a little more aggressive.

“Fuck off!” I yelled.

They drove away. On edge, Tiffany and I continued our walk to Loomis. “Don’t worry. I’ve got my pepper spray and mountain safety whistle,” said Tiffany. She was a very prepared individual.

We began to walk along the Armstrong sidewalk (D) toward Loomis (B), nervous but still pretty confident that we would get home alive. Within a minute, though, we spotted a car creeping down Cascade (E), its headlights like two cat eyes.

“Is that…them?” she said.

“No, that would be ridiculous,” I said. But five seconds later, we realized the cold, savage truth: “It’s them.”

Suddenly, the car turned up onto the curb and zoomed down the Armstrong sidewalk (D), straight toward us. Tiffany screamed, “Run to Slocum (F)!” So we ran. It felt slow and surreal, like trying to run through water. I learned what an adrenaline surge felt like in that moment, but after ten seconds I learned that it can only get you so far, since my lungs were getting parched fast. Maybe my body wasn’t fully convinced that this was life-threatening, and it was saving the ultimate adrenaline experience for running into a mountain lion while camping (this has not yet happened, as I hate camping).

As we were running for our lives, Tiffany started blowing on her mountain whistle. This was not your ordinary safety whistle that people get in handouts during student orientation. It was about as loud as a fire alarm. All over Slocum, darkened windows flicked into brightness and we glimpsed confused residents in their underwear.

After 30 seconds of running (it felt way longer), we finally burst into the Slocum anteroom (G). I turned around and saw the two men from the car rush toward the anteroom from outside. And that’s when it became clear. They had little radios on their pockets. Their beige-collared shirts had patches that read “Campus Safety.” The guys chasing us in a car were actually Campus Safety the entire time.

Now here’s the tricky part. Tiffany and I, being new to the school, didn’t know that a Loomis resident couldn’t swipe into Slocum after 10pm. As I was realizing the true identities of the men who had been chasing us, Tiffany, who hadn’t yet turned around to see who they were, was desperately trying and failing to swipe her card against the sensor box.

One of the guys was short and pudgy with brown stubble. I don’t remember what the other one looked like. Pudgy opened his mouth and said this sentence:

“My name is Richard Newman [fake name], and you don’t tell me to fuck off!”

“Dude,” I said. “We literally thought you were rapists.” Tiffany hid behind me, just now realizing it had been Campus Safety the entire time.

“You don’t belong here!” he spat back. “I knew when you said ‘fuck off’ that you weren’t CC students!”

I took my Gold Card out of my pocket and stuck it in his face. “I literally go here,” I said.

Before she had realized that it was Campus Safety, Tiffany had called 911. I grabbed her wrist and tugged it a bit to encourage her to walk back home with me. She followed me, phone still to her ear. I have no clue where the officers went. I think they probably just hung out in the anteroom and talked about how stupid millennials yell “fuck off” to mighty superiors like Richard Newman.

Tiffany and I walked into the night, past the parked SUV that had just made us run for our lives (I). It was only then I could see the dim, forest green letters printed on the side of the car: “Campus Safety.” I twitched my eyebrows. We went back to Loomis (B) and went to bed in our respective rooms.

The next morning I woke up to a phone call from then-head of Campus Safety, Oliver Holt (fake name), who I later found out had also called my mom. That’s how serious it was. I have no clue how he found out about the incident. Oliver wanted to meet with me ASAP.

He apologized, but it was clear that he was just trying to do damage control. Oliver made excuses for Richard Newman, claiming that he was just trying to be friendly (he did admit that Richard Newman had failed at this endeavor). He also promised that everyone was about to undergo excellent staff training. I suggested that they change the color of the Campus Safety car so that people could actually see that it was the Campus Safety car. They finally did this about three years later.

The next week, I got a follow-up email from Oliver Holt. An excerpt:

“We also called a mandatory meeting with all Safety staff last Thursday morning to discuss a number of issues related to making sure that our focus remains at all times on the welfare of our students, on providing excellent customer service, on the importance of language in our interactions with others, and the importance of making good decisions…although we did not discuss your incident in particular, we spent quite a bit of time talking about what good customer service looks like.”

This didn’t do much to assure me; the damage was done. I only realized how destroyed my relationship with Campus Safety was three years later, at a dorm hall meeting. My RA asked everyone if they had Campus Safety in their phones; I was the only one in the room who didn’t. Whenever people mention “Campus Safety,” I only hear “Campus Danger.”

So yes. This happened. To an innocent freshman, here at the luxurious institution known as Colorado College. Richard Newman got demoted and had to ride a bike. Neither he, nor Oliver Holt, work here anymore.

The thing is, I don’t mean to diss Campus Safety. I’m sure they’ve done a lot of great things for people over the years (although I have no clue what these things are, since I never used Campus Safety’s services due to my aforementioned incident).

What I’m really saying is: no, college isn’t the diverse, studious, blissful knowledge utopia that my college counselor sold me on. But he was right about one thing: college is eventful. Though I may have not experienced the “hall bowling” he described (I forget what he said it was, but I think it involved using humans as bowling balls), I have experienced a lot of chaotic events. There was the time a friend and I bought “gas and bloating relief tea” at Mountain Mama and snuck packets into the tea box in Rastall throughout an entire semester. There was the time another friend and I broadcasted our SOCC show through a fire drill, not even bothering to plug our ears. And then there was the time that my coworkers hacked into a suspicious email account and tried to frame me for sending weird emails because the account had Google searched the name of my high school. (It’s a long story—you can email me for the whole thing.) And of course, there was that time that Campus Safety made me run for my life.

I don’t regret any of this. I’ve come to love it. College may not be the wonderland I was promised, but I think chaos is the next best thing. Now, though, I must say goodbye to this strange life. I will soon leave CC and walk into the horizon of adulthood, a sterile purgatory where everyone works at a desk and has to remember to take out their trash in the evening. Or so I’m told.

A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing

On the Netflix show “The Fall,” Stella is a gritty British detective whose dry loathing of men is nearly palpable. She is tasked with catching a serial killer named Paul Spector, who has almost every aspect of privilege imaginable: white, male, straight, attractive, and upper-middle class. Aside from his troubled childhood in foster care, he’s practically impervious to large-scale systems of oppression, which makes him the perfect candidate to be a serial murderer of young, powerful white women.

“The Fall,” a gripping three-season saga, reveals just how creepy and grotesque serial killers can be. But there’s something that sets this show apart from your average serial killer show.

As the scene I’m watching stiffens, Stella’s co-detective, Jim, enters the room. Jim and Stella have a history: they had an affair, and Stella eventually moved on and advanced in her career. Now, coincidentally, she and Jim are working together on a case. Stella has made her standing with Jim very clear—strictly professional—but Jim doesn’t know how to take “no” for an answer. In the previous episode, he had showed up at Stella’s door in a drunken rage and tried to coerce her into having sex. So now we’re 32 minutes into season two, episode six, and Stella and Jim are preparing to interrogate Paul, when Jim provides a stern proverb of caution to Stella. Jim says Stella is about to come “face to face with pure evil.” According to Jim, Paul Spector “is not a human being; he’s a monster.”

Stella responds, “Stop, Jim, just stop. You can choose to see the world like that, but you know that it makes no sense to me. Men like Spector are all too human, too understandable. He’s not a monster; he’s just a man.”

Jim retorts, “Well I’m a man, and I hope to God I’m nothing like him.”

Stella claps back with a feminist ass-whooping and says, “No Jim, you’re not, but you still came to my room uninvited and mounted some sort of drunken attack on me...What did you want? To fuck me, nail me, bang me, screw me?”

Jim stands there, looking pitiful, pasty, and teary-eyed, while I sit in awe, shocked that this actually happened on national television. Stella had forced Jim to recognize the link between his own masculinity and the killer’s.

Stella has made a striking connection that many people are too privileged, ignorant, oblivious, or cowardly to grapple with or even acknowledge: no one is separate from the large-scale systems of oppression that silence and marginalize certain identities. To alienate yourself from this truth means you are embedding yourself deeper in complicity, blind to the fact that you are part of the problem.

In this specific context, Stella is distilling what is called the Continuum of Violence (COV). This is a concept used to illustrate how facets of rape culture contribute to systemic violence against women. The COV can also be applied to other oppressive systems regarding race, class, sexuality, religion, and ability. Now, I realize that this is a daunting concept to reconcile, which is why when Jim had his ass handed to him by Stella, you could truly see his masculinity shrivel up and retreat into his testicles. But that’s why I’m trying to parse this out. Frankly, recognizing where we fall on the COV is an emotional process, particularly for people who consider themselves liberal or progressive, because these value systems supposedly support the liberation of marginalized identities. Moreover, the COV requires us to examine the more tedious, minute, and intimate parts our lives and ourselves. When liberals look at the COV, we have to figure out ways to actually live our theoretical progressive discourse.

Toward a Better Understanding of Violence

The COV is an illustrative conceptual tool that allows us to classify and connect acts of violence in order to recognize them on a systemic level. The Continuum of Violence Against Women was the first and most widely accepted rendering of the COV, but the COV can be applied to many systems of domination and power.

If you Google the Continuum of Violence, the images that appear address violence against children, women, the disabled, racial groups, and other marginalized communities. The COV was coined by Liz Kelly in her acclaimed book “Surviving Sexual Violence,” in which she clarified that violence against women was not merely episodic behavior that arose from crimes of passion, but rather a symptom, and even a function of, an oppressive, gendered system. The COV does not create a hierarchy of severity. Rather, it shows how violence manifests in different forms: verbal, emotional, psychological, and physical acts. The continuum is meant to show how each of these forms of violence connect on both a small (daily, passive, inadvertent) and large (historical, active, purposeful) scale. (See Figure 1).

The COV describes a system of power and control that perpetuates the normativity of identity-based violence—violence that is perpetrated against a person or group due to their race, gender, sexuality, religion, ability, age, nationality, or political affiliation. Figure 2 is a telling graphic created by the Washington Coalition for Sexual Assault Programs. The bubble in the middle that says “oppression” denotes the importance of recognizing intersectionality as a context for Continuums of Violence.

The most important thing to understand about the COV is that often the acts of violence on the more insidious, micro-aggressive end of the scale are what allow the acts on the more overtly hellacious end of the scale to persist. According to the COV, identity-based violence works much like a sickness. The symptoms often show up gradually, but if left untreated, even a slight cough or an occasional sniffle can turn into pneumonia. The same applies to seemingly harmless norms like catcalling. If these behaviors are left untreated, they develop into a disease like rape. Unfortunately, we are all carriers of the disease, and the symptoms are so common that we forget that they’re products of a sickness at all. This is why the COV is important for processing how mundane microaggressions can eventually accumulate, escalate, and normalize violence.

To be clear, the COV does not rank acts of violence. This does not mean that more “minor” misogynistic practices are always equally traumatic as rape and murder, but that these actions are equally relevant in perpetuating identity-based violence. Moreover, disrupting misogynistic practices matters just as much as disrupting rape and murder because the permission of the former is what allows the latter to thrive. Everything on the continuum is deeply linked. The COV serves to complicate the notion that violence is a cut-and-dried hierarchy.

Let’s transport this into context. You are standing in the kitchen at a party and you make a joke about how all black women have big asses. This joke plays into the stereotype that all black women are sexually deviant and aggressive, thus reducing them to sexual objects. A bystanding man overhears this joke, laughs, and continues to the dance floor, where he spots a black woman wearing a tight dress. He grabs her ass without asking, as a joke, and no one says anything. A bystanding straight man watches this interaction, and it turns out he has a black girl fetish. He goes home that night with a black woman. When they get back to his place, she kisses him goodnight, and tries to go home, but he wants black ass. Despite her repeated attempts to say “no” to his sexual advances, he says, “I know you want it.” He forces himself on her. Don’t all black women love to have sex anyway?

This is obviously an accelerated version of the way that social norms escalate violence, but there are three lessons to glean from this scenario. First, the links between each act of violence aren’t always conscious. The man who overheard your joke may not have actively recognized that your words influenced his actions. Second, whether you like it or not, your joke catalyzed identity-based violence. On an individual level, the joke itself does not inflict the same amount of harm as rape, but it is just as harmful in contributing to a grand scheme of violence. Lastly, your actions and inactions have consequences, and they can harm others actively and passively. Your joke about black women signaled to others that it was okay to inflict harm. I’ve heard people argue, “Well, people with violent urges to rape are always going to rape,” and that may be true, but your joke gave others a get-out-of-jail-free card—a sign that says, “You won’t be vilified for your actions.”

I’ll complicate the hierarchy notion even further by providing some personal context. I am a queer black woman who has spent most of my life in predominantly white, liberal spaces. I have experienced racism of all kinds, but the kind that has caused me the most harm has been at the hands of people who claim to be my friends, lovers, and partners. I have had conservative strangers and peers violently threaten me as they call me a “fat ass ugly nigger.” I have had men physically intimidate me while they make transphobic comments. On the other hand, I’ve also had close friends tell me I would be prettier if I had “normal” (white) hair, and I have had lovers fetishize me until I didn’t know myself anymore. While those overtly bigoted, physical altercations left me literally wounded, they didn’t leave lasting harm on my dignity in the way that my experiences with those close to me did. One would assume that my physical altercations would outrank the seemingly non-violent moments in my life, but that’s not the case. Using a continuum, rather than a hierarchy, allows survivors of all types of violence to claim and understand their pain in the way they choose. And it forces everyone to recognize the violence within their actions, even if they aren’t rape and murder.

The Illusion of Distance

What I’ve noticed about progressive and liberal spaces is that we are often so obsessed with “moving forward” and heralding our affinity for change that we create a false moral gulf between ourselves and conservatives. In other words, by believing we are the arbiters of “progress,” we tend to think less critically about our own actions, as if only bigots, racists, sexists, homophobes, and serial killers can commit these acts. As if violence only manifests through KKK hoods and pussy grabs.

However, our “high-horse” is more like a “wolf in sheep’s clothing”—toxic social norms posing as progress. The moral confidence of liberalism reminds me of the fable of the tortoise and the hare: the liberal is the overly confident, forward-moving hare whose speed and intellect blinds him from recognizing his flaws. The COV allows us to close the false moral gulf we’ve constructed, and grasp the fact that acts of violence can occur in any space, to anyone, regardless of the moral high ground we think we have. The COV complicates hierarchies of violence and forces everyone to understand the ways that their actions contribute to identity-based violence, regardless of how much harm they are inflicting in the immediate moment. It clearly illustrates that we are all functioning as part of a system that has specific violent outcomes, and under this notion, liberals cannot claim to be separate from these problems. What’s more, we are participating in the problem just as much as anyone else.

Ask yourself this question: how is it that liberals manage to commit acts of identity-based violence against the very groups they are trying to liberate?

How is it that my white male classmate can theorize about the black feminist bell hooks, and interrupt me in the process? How is it that my black male friend can march for black lives, but call trans women deceitful? How is it that my white female co-worker can work at a non-profit for racial equity, and then say that my (black) opinions are unprofessional?

The recent sexual assault scandals including liberal public figures like Bill Cosby, Nate Parker, Kevin Spacey, Harvey Weinstein, Al Franken, and Louis C.K. have baffled many in the progressive camp (men in particular). But I believe that the phenomenon of identity-based violence within liberal spaces has everything to do with our failure to acknowledge the importance of seemingly small acts of violence. Moreover, our failure to incorporate this notion into our politics and daily lives has given birth to a brand of morality that holds hypocrisy at its center.

Anne Thériault, a prominent Canadian feminist, wrote an article about the ways that men infiltrate feminist spaces in order to commit acts of sexual violence. She notes that their ability to commit sexual misconduct hinges upon their feminism because “they get to enjoy a special status as one of the good guys fighting the good fight, they have access to vulnerable women who think they are a safe person, and finally they have a large group of women willing to vouch for them if allegations ever do surface.”

So yes, there are people who use their liberalism to enact identity-based violence. And yes, it’s a counterintuitive notion, but it makes sense if you understand the COV. Even if you are liberal and you aren’t committing heinous acts of sexual violence in the same manner as Louis C.K. or Kevin Spacey, I urge you to remember the central tenet of the COV: all scales of violence matter. There is no hierarchy. The misogyny enacted by your peers, friends, and classmates should be addressed as urgently as Bill Cosby’s 49 rape cases, not because the amount of individual harm is necessarily equal, but because all acts of identity-based violence uphold a system of oppression that inevitably lead to harm, regardless of whether or not you are the person to enact it. Acts of identity-based violence are perpetuated by sociocultural norms that we all unfortunately inherit, regardless of our political affiliation. Everything on the continuum of violence is epidemic, and none of us are immune.

This Sucks, But There’s Hope

I’m sure my previous sentence just made you feel a bit queasy about the state of society. Trust me, it gives me a sort of existential nausea too. But the goal of this article is to reflect deeply enough to shake our conscious ground, but eventually resolve with steps to move forward. So I’ll end with four main points:

First, the COV can be used as a template for understanding many systems of domination. For example, the racism scale (see Figure 3) is another conceptual representation of the COV. The COV transcends power structures, and you can use it to continuously identify violent symptoms, and unlearn them.

Second, you can try to embed the concept of the COV into your daily life. Granted, this has the potential to consume you until you start seeing tiny acts of violence everywhere, which is neither productive nor healthy. But understanding that these behaviors are happening everywhere, by everyone, is important. The COV can be empowering. Our most mundane actions and interactions have power and purpose, especially if you are someone who gains power from identity-based violence.

Third, your ability to recognize the impact of interrupting daily acts of violence holds more power than showing up to one or two protests. Identity-based violence is not episodic, but systematic. So if you can make your activism more systematic and less episodic, you have more agency for change than you think. With the ideas behind the COV in mind, you can examine power dynamics in your significant relationships and friendships. Ask the people in your life if they’ve ever felt unheard, belittled, or undignified because of their identity. You can be more critical and mindful of the images you post on social media. Do they serve to normalize violence against a certain identity group? Do you co-opt imagery and identities from people who suffer from identity-based violence? You can engage more critically in classroom settings and collaborative spaces. Are you silencing individuals who are threatened by identity-based violence?

Finally, we’re all in this together. Chances are, you are part of the problem, and so am I. While there are certainly individuals who contribute to identity-based violence more than others, we each have to continuously hold each other accountable for actions every day. We can actually get shit done if we all come together and do it consistently. Don’t just rely on the most marginalized people in your life to do it. And don’t just do it for a week after you read this. Do it all the time. Set a reminder on your phone. Write it on a sticky note and post it on your bathroom mirror. Bottom line is: do better. Don’t just say it. Do it.

A version of this article was originally published on Abram’s blog, “Living Discourse.”

Michael Sawyer's New Canon

I walked into the first class I took with Michael Sawyer thinking that I would escape the traditional Western “canon” and read authors other than dead white guys for once. The class was about Ralph Ellison’s novel reflecting on blackness, “Invisible Man.” But somehow, I also found myself reading a novel by Herman Melville and watching the sci-fi film “Ex Machina.” The purpose of these assignments was to connect the philosophy of black subjectivity to artificial intelligence. It might sound absurd, but Sawyer weaved it all together seamlessly. This is a typical Michael Sawyer experience.

Sawyer is able to tie together countless disciplines in part because he has an almost alarming number of degrees: a bachelor’s degree in political science and aerospace engineering from the Naval Academy, a master of arts from the University of Chicago’s Committee of International Relations and International Security Policy, a master’s in French and German comparative literature from Brown University, and a PhD in Africana studies from Brown University. Now, Sawyer is a Professor of Race, Ethnicity and Migration Studies at Colorado College—and unsurprisingly, uses ideas from nearly every other academic discipline. Last spring, he was awarded CC’s Lloyd E. Worner teaching award.

Here, Sawyer gives us a look into how exactly he got here, and what it all means.

Maya Day: You’ve had quite an unconventional career and academic path. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Michael Sawyer: Yeah. I have a hard time holding down a job. I went to the Naval Academy, so the requirement is just like it is at the Air Force, where you have to be a naval officer for a period of time. I was a cryptologist in the Navy, and I worked in counter-terrorism, primarily. And then I worked at the National Security Agency for a little while—while I was still in the Navy. When I got out, I came back home to Chicago and I started working at Bear Sterns at the fixed income department.

I spent almost a decade and a half working at Bear Sterns, then JP Morgan, and then I was running the sovereign fund for the President of the Gabonese Republic. That all came to a halt when President Bongo passed. Working at Wall Street, I was in an emerging market, so I got to see a lot of things. I spent a lot of time traveling in Africa and the Middle East and these kinds of places, so I was able to see many things up close that interest me from a perspective of revolutionary thought and its relationship to capital and social justice. Then I went back to school. Somehow, I got accepted into this PhD program at Brown. I wanted to work at a small liberal arts college, so that was the goal of coming back.

To other people it seems pretty strange. But to me, it all fits together; it all makes sense in this weird kind of way.

MD: Did you have any ethical qualms with being in finance, or the military?

MS: Yeah, absolutely. It’s a profoundly unethical business—both places. I was in the Navy during the First Gulf War, in Somalia, and these kinds of places. Being someone who was curious about the role of the United States as an imperial and colonial power, I got to see that up close and personal—and from a perspective of being this representative of “the Other.” I’m from inner-city Chicago, so seeing both the environment and the people who were typically in the Navy were all very different experiences for me.

Then Wall Street—what I knew about the way most people who work on Wall Street was zero from the way I grew up. In any profession, there should be ethical concerns, but Wall Street is particularly difficult—just like being in the armed forces was particularly difficult—because what Wall Street is about is producing money. That’s what the job is. You can do that ethically, but the environment around you is very difficult to find your way around and be comfortable in, socially and intellectually and ethically.

MD: What was your reasoning behind switching from finance to academia?

MS: I went to a Jesuit high school, and I had a couple of teachers that were really important to me when I look back on it. They seemed like pains in the neck at the time. Brother McKaid was this Dominican monk. He was a Kantian. He studied Kant really closely. My first track coach in high school was a Jesuit priest who had two PhDs—one in physics and one in philosophy. This is what Jesuits do. This is when I was a teenager, so we would have these conversations; they would ask me these questions, and then send me off to read stuff, and I would read it, so I never really stopped reading philosophy and theory, my entire life. I would be sitting around reading Kant’s “Critique of Judgment,” and I didn’t have to. No one was forcing me to do it.

Coming from the Naval Academy, where I studied engineering and political science, I didn’t really know there was such a thing as philosophy. I wasn’t really aware where professors came from until relatively long after I got out of college. So I never really thought about it like that. But I was reading and thinking about these things anyway, so when I decided to go to graduate school, it was more of a realization of the spaces and places where other people were doing the same kind of thing. It was a comfortable environment for me.

There was a time, I remember specifically, when I read nothing but Wall Street documents for a couple of years. I went back and tried to read “Macbeth,” which I really enjoy, and I was having a really difficult time. I was like, this has to stop. I had to go back to reading because I had become stupid in particular ways, because I was only reading documents in a particular way, not exercising my mental capacity.

So, long story short, I never had a job that seemed like work to me. I’m never like “Oh, man gotta go to work.” When I was in the Navy it didn’t happen and when I was at Wall Street it didn’t happen. I’ve been fortunate to be able to move from one thing to the next without there being these difficult points of transition, so that’s really been a blessing. That’s really been based upon what my parents did by sending me and my brother to that private school, because in the place we grew up, the schools were awful. So that’s attributable to them, more than any kind of my own aptitude.

MD: What’s the craziest thing you’ve had to deal with in each of your jobs?

MS: Let’s think. Wow. When I was in the Navy I was a cryptologist, so my job was collecting signals intelligence from the ground, so I’ve ended up in some very weird places. I was in Mauritania a couple times, which was like, “What am I doing?” Somalia was particularly difficult because it’s this state that’s falling apart and there’s this presence of warlords and this poorly designed relationship with American imperial power—trying to “assist” these people to establish a nation-state is crazy in a lot of ways. I was ready to go home.

Then, working on Wall Street it’s just every day. You look back and just can’t believe what was going on because, you know, a lot of this stuff is a culture in itself. So once you introduce yourself to it at a particular place and time, you see and hear things you can’t imagine, being a person who is self-consciously and self-referentially black. I was in a meeting with the people who run the largest hedge funds on earth, before the mortgage crisis, and literally the CEO did not know that mortgages under $250,000 were anything except investment vehicles. Like, he literally believed people were only getting mortgages for a quarter of a million dollars as some type of investment stunt because they just didn’t want to spend their cash on the house. I was sitting there… like I can’t believe I’m listening to this person who thinks there’s a 0% chance of default from mortgages under $250,000 because he thinks everybody’s got at least $250,000 in their bank account. I just found that to be completely insane. That was kind of wild.

And every day at CC is crazy. The thing at CC is that you never know what’s going to happen once you start a block.

MD: I’ve noticed that in your classes, you often use “traditional” canonical thinkers such as Hegel and Melville, but you often use them to build upon radical ideas that fracture the canon in which they exist. What is your stance on having students read traditional texts, especially in a time in academia that is against reading “dead white guys”?

MS: You make it sound like taking medicine, right? I have this conversation a lot, because every block or so, a student comes to me from some other department and they’re like, “I’m tired of reading dead white people. I wanna focus on African American literature.” And I’ll say, “That’s great, but you’re going to have to have that canon under your belt in order to understand what someone like Toni Morrison is doing.” Morrison is a classicist, and I don’t have to say it, she’s said it herself. I mean, she can’t live without Melville, Shakespeare, and Faulkner. This is one of the mysteries of the African diaspora. Those similarly situated are always working in an oppositional environment, so when we develop literature or philosophy or theory or art, it’s within a context and, to an extent, that context is a particular mélange of social forces that has been pushed onto these bodies.

So if you’re a person who’s pushing on the canon to transgress it, you probably ought know what its four corners are. I don’t want to be running around thinking that I’m saying something innovative when I’m like, “Democracy is a way to subjugate people,” and think that I’m saying that, when Plato said it. So out of Rousseau’s “The Social Contract,” we’re able to understand where oppression comes from, and then we can understand the ways in which to develop technologies or thinking to push against this.

So I’m completely resistant to “dismantle the canon.” My question is more how to expand the canon. There’s no reason why Fanon shouldn’t be read in philosophy departments, political theory departments, psychology departments, and not just in a race and ethnicity department. I don’t think you can read Fanon and not understand his close reading of Hegel or Heidegger or Merleau-Ponty or Sartre or Kant or Freud. To the extent that you don’t know that, your reading is going to be deprived in certain ways. It’s almost as if reading these “dead white people” is framed as this kind of Vulcan mind control, as if then you’re not able to think about yourself in any other way. I think we’re smarter than that.

MD: Going off that, do you think that your role here as a professor is different due to you being black and from an underrepresented background?

MS: Absolutely. Anybody who pretends that’s not true is not telling you the truth. It’s a complex thing, because at the same time that the demographics of students have been changing at Colorado College, the demographics of faculty, administration, and staff are also altering. So many of the struggles and points of discomfort that students feel, faculty feel at the same time.

I view myself as being in the position of protecting students, academically and socially, as best I can. I’m not here to be the counselling department, but I am here to kind of introduce them to a particular type of education: what does it mean to exist in this world in this way, embodied in the way that you are? Whether it’s race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, or gender, there are going to be forces that you’re going to have to learn how to resolve, and some of that comes from reading things and learning what they are, but you also have to develop a way to protect yourself at the same time. So these are very complex conversations, and as a black male professor at a predominately white institution, you have a particular role. The same would go for any professor that represents an underrepresented group.

MD: I heard that you’re working on something with H. Rap Brown [a former chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee when it was allied with the Black Panther Party].

MS: Yeah. When I was in grad school, I was working on my dissertation, and I got to this point where I was thinking carefully about black radical thought post-Malcolm X, as it relates to Fanon. H. Rap Brown—he’s changed his name to Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin—is a theorist of radical black thought, so I wrote him a letter while he was in federal prison and he wrote back. So we’ve been doing this long conversation talking back and forth. Then I got this call one night. It was like, “it’s H. Rap Brown on the phone,” so we just talked for a little while. You can’t call him, so you write and wait to hear back. It’s difficult because he’s doing life in prison for the attempted murder of two police officers in Georgia.

What we’ve been working on together is a series of reflections on Malcolm X. I’m trying to be careful to preserve his access to his rights because he’s ill—he’s terminally ill with cancer—so I don’t want him to lose his last relationship he has to speak to people outside of prison by asking questions that could have him censored or thrown off. The only reason he’s in federal prison as opposed to state prison in Georgia is because the Georgia prison official determined that he would be—at 70 or 80 years old—too controversial for the states. Only the federal government could potentially keep control over what he’s doing. So, it’s an interesting interaction.

The working title of the project is “The Book of the New School (H.) Rap Brown Game.” Chuck D [a rapper who created political music in the ‘80s] uses that in one of the “Public Enemy” records, where he talks about H. Rap Brown as this type of radical. I’ve really learned a lot from talking to him, once I got past being struck by having him on the phone.

MD: You’ve also brought a lot of interesting people to CC. Can you speak on that? Who have been particular favorites that you’ve brought here?

MS: Yeah. It was really interesting to have Flores Forbes here, who was the youngest of the Black Panther executive committee. His book “Will You Die with Me?” talks about his days as an enforcer and literal assassin for Huey Newton for that period of the Black Panther Party. Flores Forbes is somebody that speaks with a certain authority, as opposed to being an academic talking about it. Percival Everett, a novelist, has been here a couple times. His books are important in approaching questions of black subjectivity, intersubjectivity, interdisciplinary thought. His book “Erasure” is basically about a black novelist who is writing about Aeschylus and classical literature and is disallowed from doing that, and how that individual has to then write basically a stereotypical “hood” novel in order to get money and be paid attention to. I brought my friend Kahil El’Zabar and his trio to visit last year. We’ve been friends for a long time. He’s been Downbeat Magazine’s percussionist of the year several times, and he’s worked with Pharaoh Sanders and those kinds of people in the span of his career. I grew up on the 112th street of Chicago, so I grew up on the same block as Malik Yusef, the poet. He’s won a couple Grammys, he wrote some stuff on Beyonce’s “Lemonade,” for Common, and those kinds of people, like Kanye West. So Malik Skyped into our class and talked about his relationship to hip hop and spoken word.

I’m just fortunate to have all these people as friends. The thing about these people is that they are more interested in talking to students than you think they are. There’s one way where you’d be like, “Oh, this person would never want to be bothered…” but it’s fascinating how much they get from that energy. The ability to talk to smart people who are from a different generation keeps ideas fresh for everybody. I’ll try to keep doing that.

MD: What was the hardest part of your academic career journey?

MS: It’s the balance. Balancing thinking transgressively with the canon. I don’t speak traditional African languages. I didn’t study at the University of Timbuktu. I’m a very traditionally educated person: Jesuits, the Naval Academy, University of Chicago, and Brown. These are not outside the mainstream institutions.

Like, I like reading St. Augustine, I really enjoy it. I enjoy what St. Augustine was saying back in the 300s when he wrote “City of God.” So the question is, “how do we then use that in our contemporary moment to create a type of transgressive political project for transgressive ways of thinking? That’s probably the hardest thing—not even the hardest thing. That’s the thing when you really get down to it. That’s what we’re up to.

So it kind of performs itself in certain ways. That’s always been the biggest challenge. Even intellectually, when I was in grad school, I was lucky being able to go to Brown, where they didn’t have disciplinary boundaries. So when I finished my basic courses in Africana studies, I was never over there anymore. I was in comp lit, I was in philosophy, in the German studies department, I was taking religious studies classes, so I was trying to absorb this information to create a particular type of intellectual genealogy that then I could use to think about things differently. Understanding the roles of cultural limitations and the limitations of the ideas that have been introduced to me: that’s the challenge.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Performing for Ourselves

I am walking down the hill, out of the bubble of Horace Mann Ivy League Preparatory School and into the rest of the world. I have just enough time between classes to walk to David’s house, smoke a spliff, and listen to whatever new music he’ll make me listen to. His grimy Bronx apartment is a welcome reverie after my high school’s pit of anxiety. I open the unlocked door of his apartment and creep into his room. He’s sitting where he always is, legs crossed at his desk, hammering at his Korg keyboard. The sound coming out of his headphones is audible from five feet away. At four hundred dollars, the keyboard is by far the most expensive thing he owns, and more precious to him than anything. He’s hunched over, barefoot, his hair and hoodie unwashed. As always, it takes him a few moments to notice me. I wait, not wanting to break his musical trance, and sit on the edge of his bed.

Suddenly, he turns around. “Kat! Listen to this shit.” Still half-entranced, he rips out his headphones and lets the beat bump through the speakers. It’s mediocre.

“Dude! Fucking sick,” I say, “who are you writing this for?”

“Akilah wrote something last night, needs a beat. I’m trying to get it on SoundCloud before the show this weekend.”

I almost flinch—I’d entirely forgotten that we were going to perform.

I feign excitement: “Oh sick, yeah, I’ve been working on some poems, I’ll send them to you.” David doesn’t need any more negativity surrounding the performance.

At the biggest show we ever played, only twelve people were in the audience. We had been practicing for weeks. My piece was by far the easiest—I read a couple of old poems and helped the musicians move their equipment. David’s jobs were far harder. He was the one responsible for organizing group practice. It took place in the Sweatshop, a twenty-dollar-per-hour studio in Bushwick, away from the ears of complaining neighbors. He was the one who had to fight with venue managers over the money we had to scrounge up to use the space. Most importantly, he had to keep us from turning our anxiety and anger against each other. FreeThe was a hotheaded DIY group, a collection of artists desperate for success. Bickering was inevitable, just another part of the operation.

It took me a while to comprehend why he put so much effort and suffering into what would end up being a mediocre, unpopulated show. As a side performer—primarily just a friend who was invited to participate—I always felt distant from the group’s drama. From my perspective, it was almost depressing to watch. It was pretty clear that no one in FreeThe was about to make it big.

Recently, I asked Jake, a fellow former FreeThe musician and longtime friend, why he thought David worked so hard for the group. “No idea,” he replied. Jake, like me, left the intensity of New York for the quiet emptiness of Colorado. I think he still harbors some resentment for the city and its people.

“It’s like, when we performed,” he continued, “it would just be going terribly and we knew it was going terribly but we just had to pretend it was all okay. We just had sit there and cringe.” I was surprised to hear him speak so negatively of FreeThe. “Why didn’t you quit earlier?” I asked. “They’re good people and I need good people to practice with,” Jake said, before changing the subject.

After David and I finished our spliff, the initial edge of pre-show anxiety disappeared, and my excitement was a bit less forced. He continued to work on the beat as I leaned back and listened, willing it to be better, desperately hoping for him to succeed. Perhaps it was just my affection for him and my own wishful thinking, but after fifteen more minutes of work, the beat sounded halfway decent. I lay back on the bed, soaking up a bit more of David’s ardor before trudging back to class.

Jake’s answer to my question was unsatisfying, so I’ve been searching for a better one. Why did David work so hard for what he must have known wouldn’t succeed?

Only recently, now that I’m more than halfway across the country and dearly missing FreeThe, have I begun to realize that the question of “why” never even entered anyone’s head. We only wondered “how.” The group’s need to make art was not up for question. Our only focus was finding a way to do what we needed to do.

That’s why we put on shows: It gave us a deadline, a tangible reason to get together and practice. Though most FreeThe members would deny this (they’re as haughty as most artists are), the show didn’t matter nearly as much as the practice. We did it for the process, for the actual production of art. The show itself was only a byproduct.

In David’s case, there is another factor that can’t be overlooked. Before FreeThe, back when I only knew him as an older guy with a slightly predatory reputation, he was a weed, cocaine, and acid dealer. He’s only told me the story of his downfall in various hesitant, drunk fragments—it’s a touchy subject for him. Essentially, he was robbed of a few thousand dollars’ worth of drugs and needed to get the money back fast. After making some bad decisions to get money quickly, he wound up at Rikers Island prison for a brief period of time. Since getting out, he’s remained relatively clean and has only worked legal jobs.

FreeThe was partially a distraction, something to fill David’s time so that he didn’t feel as compelled to return to the drug scene. I also believe, though, that being responsible for something made him feel better about himself. Like a parent raising a child, David could focus on the successes and failures of FreeThe to distract from his own.

The next Saturday, I was back at David’s house, clumsily taking apart a drum kit and preparing it for the nearly two-hour long subway journey to the Lower East Side. Most of FreeThe was also at David’s house, leaving little room to move around the tiny apartment. An air of excitement filled the small space as everyone hyped each other up.

I kept to the side, alone with the cumbersome drum kit—I didn’t want to bring down their energy with my anxiety. Performing has always been tough for me, though not for the reasons that Jake expressed. Once I begin to read my poetry, my fear dissipates. Every moment until then, though, is painful.

Swallowing my stress, I began hauling the drums past the broken elevator and down the stairs, allowing myself a moment alone before the inevitable ordeal of performing.

As bad as my anxiety in that moment was, it was far from the worst it’s been. In seventh grade, I shared a piece of writing with a large group of people for the first time, and became so overwhelmed with fear that I cried. I ended up having to leave the dingy public library auditorium. Years later, after winning a competition for a piece I wrote, I was so anxious about reading it publicly that at the last minute I backed out of my opportunity to perform at Carnegie Hall. Instead of going to the ceremony, I watched a live stream of it with my parents. I remember staring at the screen, still dressed up in preparation to perform, filled with regret. I decided to never let it happen again.

Like me, David and the rest of FreeThe were kids on the cusp of being “real artists,” willing to put in whatever amount of pain and effort required to make something beautiful. Also like me, they often failed to actually do so. Either way, they were there to force me to continue to try, and I was there to force them. They gave me the tough love I needed. Once or twice, Jake angrily yelled at me to “stop being a little bitch, Kat” when I tried to get out of performing. At the time, I hated him for it. His aggression felt cruel, and amidst the group’s usual bickering, I took his insults personally. But I realize now how much that anger helped me. Nothing but the bitter desire to prove him wrong could have made me get up and perform.

The subway ride from David’s house in the Bronx to the lower Manhattan venue must have taken an hour and a half, and with a drum kit, keyboard, guitar, and pedalboard in hand, it was a hellish excursion. Some of the other passengers smiled at us, though I’m not sure if they smiled because of the absurdity of the scene or out of warmth and respect for visibly struggling musicians. Either way, their joy was a welcome sight. Most people were far ruder, disregarding the preciousness of our equipment and callously kicking or bumping into it. I’m sure that for people like David, whose keyboard was his pride and joy, their behavior was heinous.

Finally making it to the venue was barely a relief. Moments after we got there, David was already arguing with the manager.

By 8 p.m., the drama had peaked. The issue of the venue fee had led David and the bar manager into a near-physical screaming match. Money was often the root of our fights with venues. Usually, a band will pay a certain amount of money to play at a venue, and the money is returned after ticket sales. At this particular show, the venue refused to return the hundred dollars that we had barely managed to scrape together from painful extra working hours. We couldn’t afford to lose that money.

Not all of New York’s teenage performance groups go through this struggle. Certain groups whose families have the money to support their music can easily afford to spare a hundred dollars. Often, they can spare even more, which gives them the option to play at bigger venues with better advertisement and regular crowds. Money isn’t the only key to success in DIY, but it certainly helps, and our lack of money certainly put us at a disadvantage in the harsh competition of the New York music scene.

New York is overcrowded with talented people trying to make it, to stand out against the masses of equally talented performers. The city is simply too physically dense to accommodate us all. Because of this, performers are forced to appeal to the economic interests of venues, which, as much as they want to help the art scene, also need to sustain themselves financially.

For the most part, we made an effort to resist the atmosphere of tension and remain supportive towards each other. But sometimes we would slip up and let the stress get the best of us. Someone would give five dollars less than another person would, and bickering would ensue.

David left the bar in a huff. Half the group left with him to offer comfort and solutions, while the other half, including myself, stayed inside with the equipment. None of the people who left were allowed back inside. The bouncer became a barrier between the two halves of FreeThe.

When an hour passed, no solution had been reached and we were halfway into our time slot. Out of boredom and the unavoidable urge to continue making art, we began our show unplugged, with only half of the group, and without an audience. We played for each other and for ourselves, channeling the frustration right back into the work. We improvised. A guy with minimal drum experience played a box drum. I recalled my childhood ballet classes and danced. I read poems over a girl’s singing. People picked up instruments they’d never used before. Ultimately, we just messed around, giving in to the chaos of our failed show, relishing the freedom it granted us.

Half out of tradition, half out of an attempt to console ourselves for the objective failure of our show, we decided to leave the venue and get drunk. With money we didn’t make from the gig, we bought pizza and beer and migrated to our usual corner of Tompkins Square Park. It was a bit too cold and late to be hanging outside, so the park was deserted apart from our group and our equipment. Our little caravan, dwarfed by all the gear, huddled in the slight shelter that the drum kit and guitar cases provided.

No one was talking. After our moment of failure, each of us was deeply involved in our own internal debate. Why do I do this? Why am I wasting so much money? So much effort?

“I still think I should have socked that guy,” said David.

“Yeah, no shit,” said Jake. There was a pause before we all started to laugh. For the first time, I realized the comedy in the scene. I saw my underdressed and shivering friends hugging their instruments, sitting in a circle on the pavement for no real reason, pouting like children.

David mentioned something about an open venue in a couple weeks but was quickly cut off by a communal groan.

“Ok, fine. I’ll shut up.”

Our Lady of Mercy

TJ Larsen’s ears had so much earwax in them. It was all caked up in there, yellow-orange. He was a new student in the first grade and I sat next to him and stared into the clogged tubes of his ears. Everyone knew it. Someone, please, just tell him to use a q-tip. I wanted to stick one right up his ear. It would pop! through his ear drum and burrow till the cotton tip nudged his coiled brains. When I suctioned it out I’d be able to see straight into TJ Larsen’s head.

Apparently in high school TJ Larsen fucked a girl in a Macy’s changing stall. I’ve never had sex while standing up. I assume that’s how they did it. TJ hadn’t been earwaxy since sometime in fourth grade.

Laura Baumhauer had a waspy presence. Nobody really liked her. When people sat down for lunch they would always sit on the side where she wasn’t. So she’d be sitting on the end with the empty bench beside her and everyone piled up on the other side. In sixth grade, Margaret Bruge whispered that Laura stuffed tissues or maybe even socks into her bra. Margaret knew because she saw something fall out while we were changing for gym class.

Laura had acne and large pores that made her face look like a strawberry. In line at our sixth-grade classroom door I heard her boasting, “my parents have never had sex.” I told her that they must have had sex at least twice, because she and her sister existed.

Laura wore a East High T-shirt in her eighth-grade yearbook photo. She kept talking about high school. It would be a fresh start. Laura made friends at first and I think people liked her for a time before they realized she wasn’t cool.

Jess Adamson was my best friend. We walked the three blocks to Lady of Mercy together every morning and back home every afternoon.

Parents gushed over how small and polite Jess was. I felt too large. Jess had anxiety and bladder spasms. When a spasm came on, maybe on the walk to school or in the hall, Jess would crouch down on one knee. I’d crouch down next to her, and we’d pretend to tie our shoes.

Jess and I talked in the Quiet Area about how neither of our families went to church and we didn’t think God existed. Maybe there were spirits, though.

Jack—not Jack Strotman, the other Jack—Brezicki—he was pudgy and gluten-free. He threw up in front of the take-home folders in first grade. I thought he had just spilled some soup. He, Jess, and I were voted “sweetest personality” in the eighth grade yearbook.

Katherine Strauss was one of my secondary best friends. She taught me long division in third grade, which was the year her parents got divorced. She had nearly a hundred Littlest Pet Shop animals and a half-dozen Webkinz, which all went to her dad’s house. Her mom fed us carrot slices and had us make crafts such as hair-tie rugs or mosaic bowling balls. Katherine invented several languages that included code names for our classmates so we could gossip while they were still in earshot.

Sometimes Natasha Sangsorn’s father would be sleeping on the couch when I came over for a play date. Natasha had a ginormous house with a trampoline in the backyard and a walk-in snack pantry. Stuffed animals crowded her canopy bed. Natasha’s mother was overweight. Natasha went vegetarian and ate nothing but Greek yogurt at lunch and said she was too fat, but she wasn’t fat at all.

Natasha wanted us to be close friends but I didn’t like her. Once, she shunned me for a whole recess because I chose to sit next to Katherine instead of her at lunch. She had a sleepover for her golden birthday and ordered everyone not to be too loud. She created a system of strikes for our girly squeals. Natasha wanted to go trick-or-treating with Jess, Katherine, and I, but I didn’t want her to come. I made up excuses but later pretended it was all a misunderstanding when she called me on my flip phone and told me she was struggling with depression.

Emily Hagley locked herself in her room and wouldn’t come out. It was her birthday party and her mom pleaded at the door while we sat around the table staring at our uneaten slices of cake. Emily locked herself in there because she didn’t get to eat the first bite. I avoided eye contact with the other girls, my stomach tight. I was the one who had snuck the bite of cake.

When Emily came over to my house that one time she had us play Dog Show. She coaxed poor Luna up and down the stairs and pushed her through the hula-hoop. Emily sat next to me in U.S. History and kept stealing my colored highlighters. I wondered, is this bullying?

In sixth grade, Nick Nell’s hair was a blonde Justin Bieber swoosh. Every few minutes he’d twitch his neck sideways to toss the hair from his eyes. Freshman year he dated a senior and gave her a concussion against the back windshield of his car while having sex. He constantly flirted with Ms. Roderick in Western Civ sophomore year. That summer, he got into cocaine and went to rehab and came back hollow-looking.

Miranda Bellthorne annoyed me when we were paired up for badminton. She couldn’t hit the birdie. She was small, obsessed with Disney, and had her future planned out in detail. Jess liked her, though. They went to the mall together and talked about their crushes. Jess and I had never gone to the mall together because I didn’t like trying on clothes. Jess wasn’t supposed to like that stuff either. But a part of me wanted to go, too. Jess never asked me to come. I felt like she thought of me as a boy.

Oliver Raffburg was small but athletic and charismatic. He sang the song, “Build Me Up Buttercup” in front of our music class. He said that Miranda had the perfect face and body. Perfect proportions and symmetry. A long neck.

Story Walters’ desk was in front of mine in the third grade. She was absent for a week. When she came back, I saw the gauze on the back of her skull replacing clumps of her tightly curled hair. Story had a brain tumor. She was in a wheelchair at the end of fourth grade. Her face and body looked all bloated from the chemo. She died in fifth grade.

At recess once, I found a clay frog magnet in the woodchips and Story wanted to have it. She kept asking me for it, but since I had found it, I didn’t give it to her. I felt guilty about it and buried the magnet under the swings after she died.

A counselor lady came to our classroom once Story had moved to hospice. She asked us if we had any questions. “Is Story going to die?” Oliver Raffburg asked, timidly. The lady paused, then clasped Oliver’s shoulder. “Everybody dies,” she answered.

Mr. Paulson, the principal of Our Lady of Mercy, got a brain tumor a few months later and died. Mr. Paulson had a bald head and was a Bears fan and started a “walk around the world” thing where he’d walk around the neighborhood with a herd of students at lunch. If you went, you got a little plastic foot that you could put on a keychain. The feet came in all the colors of the rainbow plus brown, grey, black, and white. Some were transparent and some opaque and a few were even sparkly. He died before I could collect them all.

Caroline Lund was my other secondary best friend. She gave Jess a stuffed animal otter because “it’s a special day” (it wasn’t) and gave me an old wine bottle. I eyed the otter on the walk home. Freshman year, Caroline explained to us what masturbation was. She had discovered it for the first time with the showerhead.

Caroline got really into baking. Her cookies were the best. People would always comment on how slender Caroline’s older sister Ellie was—she could be a model! In eighth-grade she lent me a book about a girl with bulimia. I got bored and never finished it, but when I gave the book back I told her it was a good story. Years later I learned she had been making herself throw up.

During kindergarten playtime, Olivia Harris always took the role of Mother. I felt cute in my overalls until she told me in the stairwell that they made me look like a cowboy. Olivia’s older brother Tommy hung himself in his closet the night she starred in the eighth-grade play.

The next week the teachers gave us pamphlets on the signs of depression. Olivia still came on our pre-graduation field trip to Navy Pier. “Pirates of the Caribbean” played on the little TV bus screens. Mrs. Myler shut it off when the scene of the pirates hanging from seaside gallows came on.

Mrs. Firton liked having Garrett Teeler do the banana dance. He stood at the front of the class, gyrating his seventh-grade hips. At any one time, at least five girls had a crush on Garrett. When we all piled into the girls’ gym changing room for a tornado drill, Garrett pointed to the tampon dispenser and asked, “what are tampoons?”

Eva Peters was gone for a day in the sixth grade. Apparently her mom had a “girls’ day” with her because she’d gotten her period. I didn’t get my period until eighth grade. It was the night before picture day and I went to my mom’s bedroom and asked her what the brown stuff in my underwear was, even though I knew what it was. I wore a navy blue button-up shirt and khaki pants and a big pad in my underwear that felt like a diaper because tampons freaked me out and I didn’t understand exactly where my vagina was. While waiting in line for pictures, I felt the blood soak up the pad and through my khaki pants. I escaped to a bathroom stall and lined my underwear with toilet paper but I knew people had seen. I kept pulling my shirt down throughout the rest of the day. I wanted to tell Jess about it on the walk home and I knew she knew, but I never mentioned it and neither did she. Jess didn’t get her period until sophomore year.

When we dissected worms in seventh grade science class TJ made some joke about sex that offended Mrs. Myler. She scolded TJ’s offensiveness in front of the class and told us that sex wasn’t that great, anyways.