The Akito Van Troyer story

by Catherine Sinow; illustration by Britta Lam

Last semester, a man named Akito van Troyer materialized in Colorado College’s music department. I took a class with him, and he kicked it off with a Powerpoint about all the instruments and apps he had built. “This is just some stuff I’ve made,” he said casually. Over the course of class, he showed us lengthy slideshows featuring dozens of absurd music devices. Among them was a fedora-wearing robot with electronic lungs that plays the flute and kinetic sand that makes music when you touch it.

Akito seemed to have zero issues when I hung out in his office for hours at a time, asking him personal questions with my phone recorder on. I learned he was born in Portland but moved to Okinawa, Japan at the age of three. “When I was a kid I was not into making things,” he said. “I was more into moving my body more than anything. I could never stay in one place longer than two minutes.” He didn’t study in high school, and his favorite subject was PE. He ended up being selected as one of the best soccer players in his state.

Soon, the time came to take Japan’s series of life-determining college entrance exams. He wasn’t exactly prepared. “I didn’t take the exam because I didn’t study at all, and everyone knew I wasn’t going to pass any of them.” So he fled to the USA.

Akito enrolled at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, planning on an ethnomusicology major with a concentration in gamelan, a traditional Indonesian music ensemble. He wanted to study music, but avoid the Western theory he had learned while playing classical guitar in high school. But he found gamelan restrictive too, so he turned toward computer music. “If you use computers,” he said, “you can generate any kind of sound or music structure you want. You’re free from the physicality of playing that music.”

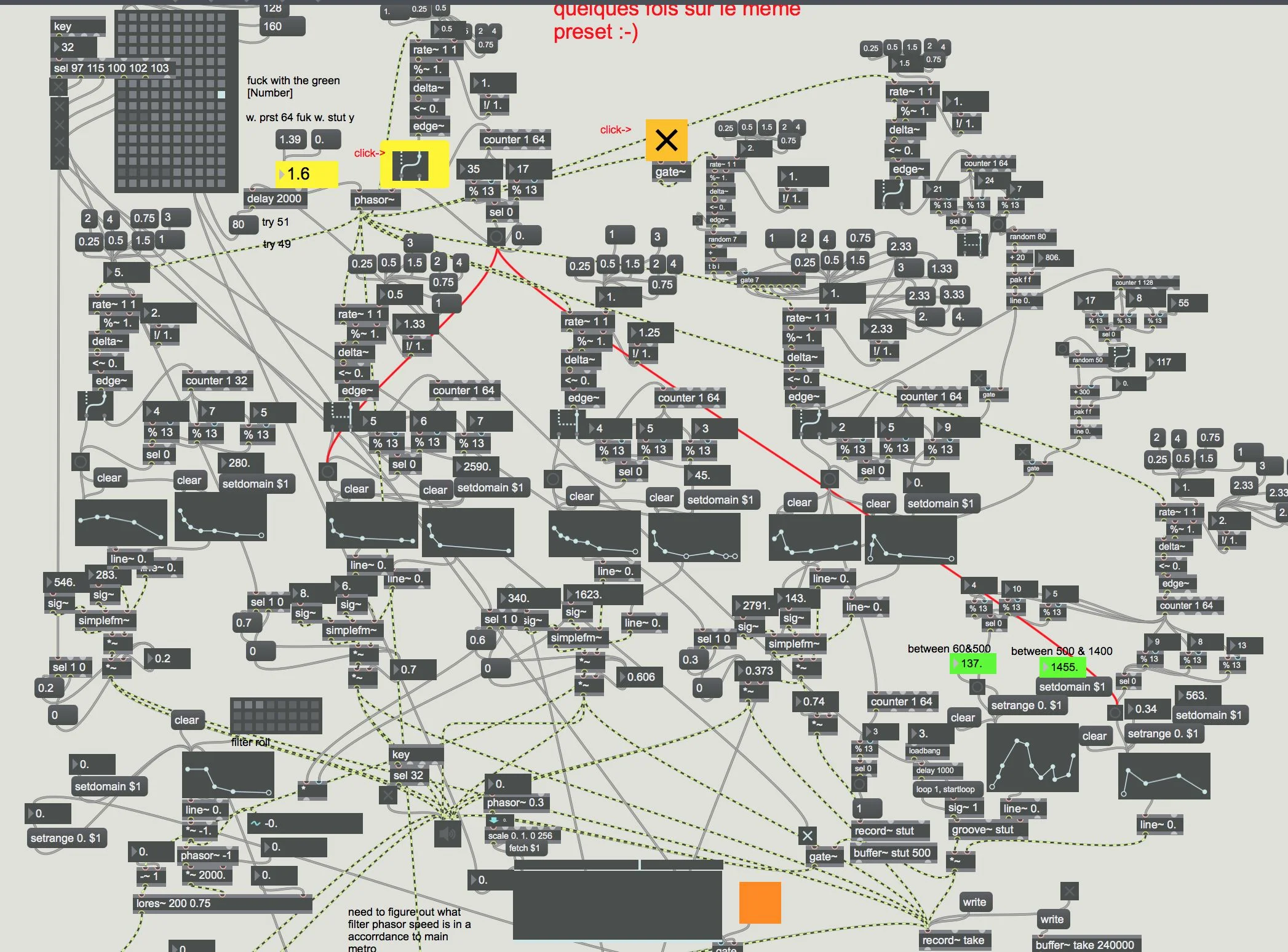

Akito mostly ignored common digital audio workstations like Ableton and Logic. With built-in synthesizers that let you compose songs in a linear fashion, these programs allow for a fairly straightforward songwriting experience. Instead, Akito became fascinated with Max, a visual programming language for generating sound. For the non-computer savvy: a visual programming language is any computer language that works like a graphical flowchart, rather than responding to text-based commands. Max is a blank slate that lets you create infinite rules and parameters for a sandbox-style experience. It’s difficult to learn, but once you do, you can program just about any sound you can dream of.

My class learned Max. Well, we tried to learn. Max, to me, is something like a legend. It’s the “Ulysses” of computer music.

Seeking total freedom, Akito bought Max and spent an entire year learning it every day. His friends always invited him to go surfing on Waikiki Beach, but he would refuse, go inside and learn Max instead.

“I don’t really like Max to be honest,” he said to me, 15 years after first picking up the program. “I don’t want to just make objects and keep patching with my mouse.” There’s a lot of mouse-dragging involved in Max. “I just want to type things.” Today, Akito usually makes music with SuperCollider, a textual programming language. While most computer musicians are playing with colorful, user-friendly softwares like Ableton, Akito is typing into a white box.

Creating a song in Ableton Live, a digital audio workstation.

Making a patch with Max, a visual programming language.

During his time at Hawaii, Akito took a lot of classes that had nothing to do with ethnomusicology. Towards the end of his fourth year, he decided it would be easiest to make his own major. So he created one called “Interdisciplinary Studies for Multimedia,” consisting of music, computer science, art and engineering classes. He graduated in 2008 after his sixth year, with about twice as many credits as he needed.

After Hawaii, Akito began his master’s at Georgia Tech. He and his colleagues attempted to create a method to play music collaboratively over the Internet. Their main focus was overcoming a 20 millisecond delay in sound transmission. The group never solved this problem. However, they were able to create methods for collaborative composition that didn’t rely on exact timing.

One of these methods became Akito’s master’s project, which involved coding as a live music performance. Working with the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, he developed software called Laptop Orchestra Live Coding. The performance videos on Akito’s website show groups of kids with computers sitting cross-legged on a stage. Their text commands appear on a projector screen as you hear corresponding changes in audio. It sounds like typical experimental electronic music from the 90s and the early 2000s, which involves a lot of percussion and emotionless bleep-boop sounds.

Akito went on to earn another master’s at the MIT Media Lab. Today, he’s still there, working on his PhD, sometimes escaping for a few weeks to teach at Colorado College. If you don’t know anything about Media Lab, you should know that it’s not your typical MIT hard science research facility. Recent projects from Media Lab include inflatable cheese, genetically engineered silkworms that spin glow-in-the-dark silk and a robot that cremates your hair and nails as performance art.

Akito’s advisor is Tod Machover, a music professor and creative mastermind who looks perpetually enthused. While researching for this article, I have stumbled upon at least 10 photos of Tod looking ecstatic about his students’ technological creations. Akito has assisted Tod with works including “City Symphonies,” a series of compositions based entirely on crowdsourced sounds and “Death and the Powers,” an opera where humans perform alongside dancing robots.

In his free time at Media Lab, Akito builds his own instruments. MIT provides a lot of resources—“Shop to laser cut things, water jet things, 3D printer, you name it”—but he also frequently loots through school campus trash bins for instrument components.

One of Akito’s inventions is VibroDome, which looks like a massive 32-sided die cut in half. Each facet is made from a unique material such as carpet or glass. The facets emit experimental and nonsensical sounds when touched; the project aims to “betray people’s expectation about a material.” Other creations include Drumlet, a small box that echos any drum pattern you tap on it, and DrumTop, a drum machine that creates its sounds by knocking whatever objects you place on top of it. However, it was one of Akito’s non-musical projects that intrigued me most. It’s called Re:Human.

“It came from a class we took about empathy,” he recalled. “Everyone was working on projects about empathy, like, how do you evoke empathy to connect strangers? I took the different route which was to negate empathy.” After learning in class that the opposite of empathy was objectification, he set out to create a project that evoked just that. “I wanted to physically induce objectification. Not mentally, cause it’s hard to get into people’s brains. So I made a floor entirely consisting of human faces. And you have to step on them.”

The tiles were inspired by Japan’s first brush with Christianity in the 1500s. “The authority in Japan at the time really didn’t like Christianity, so they started eliminating all the Christians,” he explained. “The way they tried to find out who’s Christian and who’s not was by using this picture of Jesus as a tile. The authority would make people step on the Jesus. The people who didn’t step on the Jesus—obviously Christian. They would get executed.”

In the next version of Re:Human, Akito will take participants’ phone data and project their Facebook friends onto the tiles. Of course, being very secure about his Internet presence, Akito would never consent to this himself.

While I was taking Akito’s class, I would often go to his office with Max-related questions. He would always answer them quickly, sometimes vaguely, as if to get them out of the way. Afterward we would spin off into long discussions about the future of technology, going for as long as an hour and a half.

“We’re going to make a biological computer,” he told me one afternoon. “It’s going to be like a dog or human, probably better than either of those things.”

“But it’s going to be engineered?”

“Yeah. The first one’s gonna be lab-made, but it’s going to have a reproduction system in there, so it’s going to make one of its own perhaps.”

“Will this happen in our lifetimes?”

“Very possible. It’s getting really really close.”

“I’ve never even heard of this before.”

“I hear it all the time. I go to Media Lab.”

While we talked, Akito fidgeted with a roll of tape around his hands. He kept his feet on his desk and blew his nose with a paper towel, then tried to throw it in the trash can and missed. “Do you know the DIY movement these days?” Akito said. “Like make magazines. That’s all cute and stuff, but in the near future this is going to happen in the biological domain too: DIY biology at home. You’re going to have access to all these things.”

I asked him if he’s married. He said no. I asked him if he has a girlfriend. He said yes and that her name is Rebecca and that they met at Media Lab. I later found her on Google. Rebecca Kleinberger’s projects include a dress decorated with an internal light projection system, a proposition for a series of staircases that go nowhere and a hearing enhancement device that’s basically two satellites you strap on your head. She also has a gallery on her website with photos of her pet hedgehog and her creative nail art. Akito and Rebecca do not have any children, but if they did, they would all play an interactive music game called “Fantasia: Music Evolved.” I know this because Akito announced it to our entire class.

“How would other people describe you?” I asked him.

“Possibly robots,” he said.

“Why?”

“Because I’m constantly working.”

“Usually when people call themselves a ‘robot’ they mean no emotions.”

“That’s probably partially part of it. I tend to think of emotion like a spring system. It loops, like, fluctuates. And everyone has a different level of fluctuation.”

“Would you describe yourself as a low spring fluctuation kind of guy?”

“Definitely that.”

Wrapping up the interview, I couldn’t help but regret that I had asked him such boring questions.

“I was thinking that maybe not necessarily for you, but in the future, I would do an experimental interview,” I told him. “I could show the person pictures of unrelated things and ask them what memories it triggered. Then I’d use that as the basis for the interview.”

Akito was on board. “That sounds like the logical thing to do right there. People have definitely done this before. I’m sure the NSA has a lot of documents on this.”

Block four, Akito taught a class called Experimental Music. Students made their own physical instruments and routed them through Max for enhancement. At the end of the block, they performed a concert. One kid made his own lap steel guitar and performed a magnificent composition called “For Akito.” Another student made a violin-like instrument out of a ski and bowed it with a ski pole, wearing a ski mask on stage. Another kid created an instrument from a hollowed-out Snuggle detergent container. At the end of the concert, everyone improvised together, conducted by Akito. It was a thing of true beauty.

Part of the Toxic issue