The CC grad engineering Trump’s EPA

by Sara Fleming; illustrations by Katie Lawrie and Caroline Li

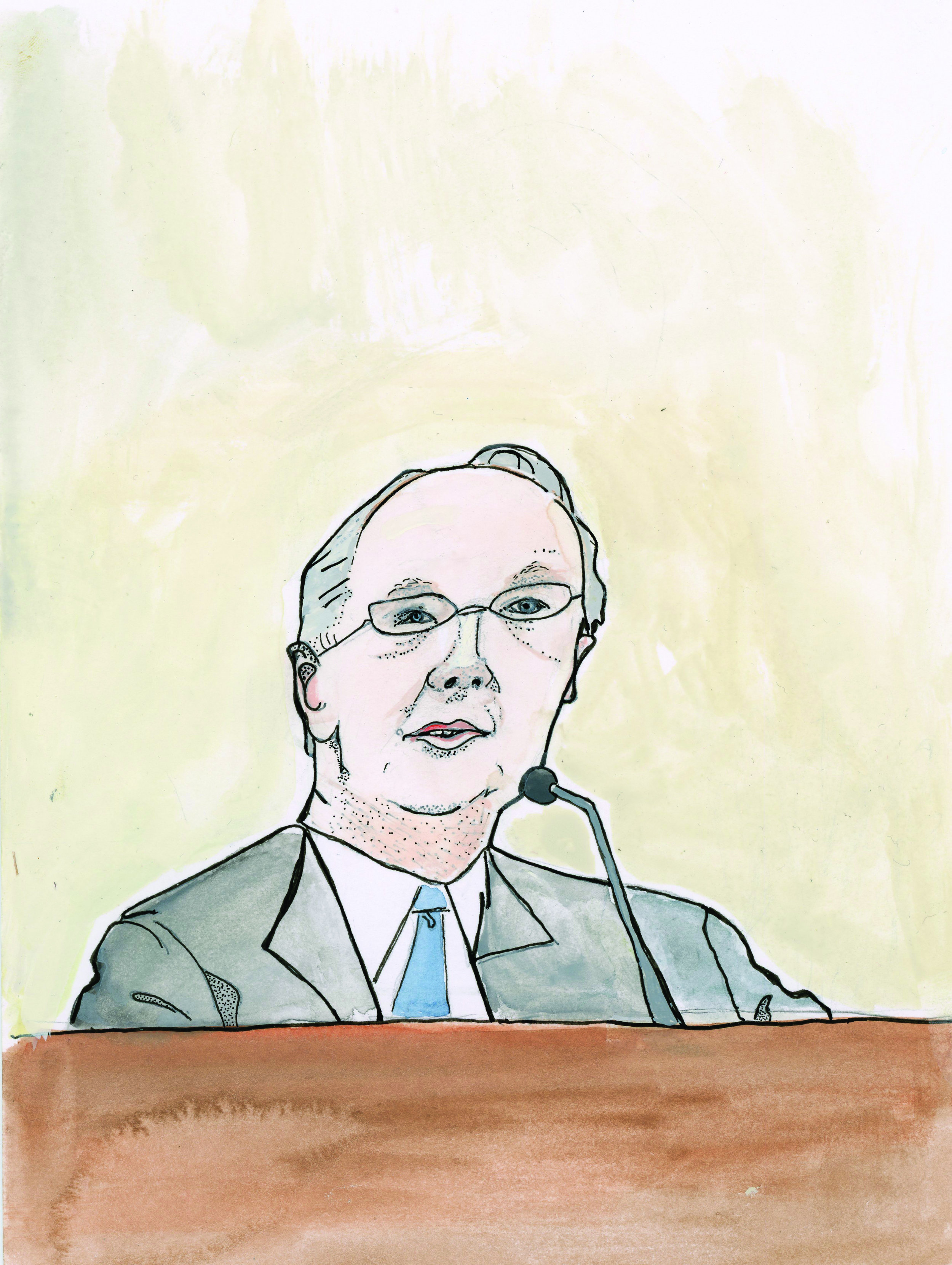

When Myron Ebell was a senior at Colorado College in 1975, he took a seminar on socialism. Today, he is one of the most outspoken conservative voices working on climate change policy, and was appointed to head the EPA for President Trump’s transition team.

Two months ago, that reality would have been almost unthinkable. It was, first of all, a shock to most that Donald Trump was elected and inaugurated as President of the United States. Then, it was shocking that his EPA pick (who has spent most of his career criticizing the EPA) went to CC, a liberal bastion with a supposedly strong emphasis on environmental responsibility. Ebell graduated with a degree in philosophy.

For most CC students, all of that information probably lies somewhere on a spectrum from sickening to terrifying. If you were aware of Ebell’s appointment, perhaps you signed a widely circulated White House petition demanding Ebell’s removal from the transition team. The text of this petition was short, simple and biting: “Donald Trump has chosen a leading climate skeptic to head the EPA transition. Do not let a man who denies science in the name of profit lead the nation in environmental protection.” Ebell chairs the “Cooler Heads Coalition” at the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), a libertarian policy organization dedicated to prevailing against “global warming alarmism.” Among numerous critiques over the years, he was profiled as a leading climate change denier in the documentary “Merchants of Doubt,” and the activist group Avaaz named him one of seven global “climate criminals.”

The portrait they painted of Ebell is not novel: climate change activists on the left tend to dismiss “contrarians” like Ebell as greedy, deluded and dumb. If this were true, it would mean that CC had failed to inculcate rigorous critical thinking skills in him. And if people like Ebell aren’t portrayed as blundering idiots, they’re demonized as ideologues with a calculated political motivation that directly threatens the Earth and its inhabitants. The latter view would mean that CC had failed to shape a sense of ethics—ironically, in one of its most successful philosophy majors.

These were the sentiments that seemed to reach CC students: how could we have produced someone who so adamantly denies a scientific issue that 99 percent of scientists agree on? After the election, there was a brief movement to petition the college to discredit him. A comment on a Facebook post in the Class of 2019 page read: “He clearly learned nothing from this institution.”

To find out if this was true, I talked to five professors who either taught or worked with Ebell and one of Ebell’s college roommates. I also did a bit more digging into the present-day Ebell (the CEI failed to respond to inquiries for an interview, but his comments and viewpoints are well-publicized). Ebell can’t be so easily dismissed as ignorant and evil. By all accounts, he was a smart and likeable student who embodies many of the qualities that CC hopes to instill in its graduates. This more complex reality has much to offer in reconsidering how we understand the college’s role in shaping figures like Ebell—and in understanding how they might operate in the coming political era. To see how, let’s go back to that first sentence: when Ebell was a senior, he took a seminar on socialism.

The class was taught by History professor Susan Ashley—Ebell would later name her one of his favorite teachers. She too, remembers him fondly: a lanky kid with a wisp of white-blond hair atop his head, always engaged in class; “a vigorous, lively discussant.” And that doesn’t mean he was obnoxiously opposed to everything about socialism. According to Ashley, “he was interested in the ideas…I expect his education really did matter a lot to him.”

Everyone I’ve talked to that’s met Myron Ebell describes him with this bemused, almost embarrassed hint of a smile on their face, as if they’re reminiscing about genuinely enjoying the company of someone who has since become an infamous figure within their own circle.

No one is exactly sure how much of this persona was instilled in him at CC, though there were a few hints. “He didn’t take what struck me as clearly conservative positions on any subject,” Ashley said. “I think where I make the connection [to his present-day positions] is that he was very much a contrarian, which made him a wonderful participant in class, because he was irreverent and provocative. He had a very attractive way of thinking about things; he was analytical and quite critical. So I think maybe that instinct on his part lined up with, or found expression in, his views now.”

Philosophy professor John Riker, who taught Ebell in one block, wrote in an email, “He was unusual in his thinking—a bit of a maverick (maybe even oppositional). Clearly, a bit odd, but bright—very much his own person.”

Others pointed to a conservative sentiment that had been brewing long before CC. Classics professor Owen Cramer described him as a “libertarian rural, small town kid from Baker City in eastern Oregon.” He served with Cramer on the Academic Program Committee, which sought to redesign general education courses. Besides being invited to the academic honor society Phi Betta Kappa, this was his only recorded extracurricular involvement.

His college roommate, Glenn Williams, who now lives in New York, had an even stronger perspective on Ebell’s pre-CC convictions. He wrote in an email, “It is my opinion that Myron was very conservative when he came to CC. What differentiated him was a kind of libertarian tinge, which put him on the side of some popular causes… His orientation was always elitist, and he tended to accuse opponents of being anti-democratic.”

Ashley remembers that Ebell hung around a circle of friends with outspoken but widely varying political views. One was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War who worked night shifts at Penrose Hospital to maintain that status. So however strong Ebell’s beliefs, he wasn’t one to shelter himself in a social echo chamber of his own viewpoints—and not academically, either.

“He had something of the gift for speaking in epigrams,” Ashley mused. “One which I remember in particular was when we were talking about the peasants in [a class about the French Revolution], and he said, ‘The peasants always get the shaft.’ And that became a refrain for the class, which, of course, would make you think he had some sort of sympathy for the masses. Which he probably did at that point.”

Beneath all of the conflicting personas, there was one descriptor of Ebell that almost everyone—the media, his professors, Ebell himself—used: contrarian. “It means that he doesn’t simply accept at face value what people tell him or what his teachers might say. He adopts positions for himself,” Political Science professor Tim Fuller said. Fuller was perhaps closest to Ebell at CC—he helped him into a graduate program at the London School of Economics to study the history of political thought under the philosopher Michael Oakeshott. Fuller and Ebell still maintain a friendship (they exchange emails and often see each other when Fuller visits DC.)

“Well, he’s very smart,” Fuller said. “He was a good student. He was very quick; capable, obviously, of forming very strong opinions about things—the sort of student that one likes to have because he was smart and serious about what he was doing.”

After LSE, Ebell did a year of graduate work at Cambridge, but returned to the United States to work on public policy. Environmental policy quickly became his focus. Here’s a sample of his track record in his first few years: he worked as a lobbyist campaigning for the rights of property owners in US national parks and forests, campaigned against regulation of the tobacco industry and once criticized Newt Gingrich’s authorization of the Endangered Species Act, saying that Gingrich’s “soft feelings for cuddly little critters is still going to be a big problem.” He has been at the helm of the coalition working to prevent policy against climate change since the late 1990s, when it became clear that the science would suggest major societal changes were needed to solve the problem. By the time George W. Bush took office in 2001, Ebell was already poised to shape a president’s—and probably an entire sector of the public’s—relationship to the EPA.

Ebell worked from both the inside and outside, contributing to a near-complete dismantling of climate change as a top issue in United States policy. He built a popular following and media presence as an outspoken critic of the Kyoto Protocol, a major international agreement to curb carbon emissions that Bush had originally intended to join (the U.S. soon dropped out of the Kyoto Protocol, prioritizing economic concerns). It’s hard to know the depth of Ebell’s influence within the Bush administration, but leaked emails indicate that Ebell directly advised Phillip Cooney, a senior White House official who edited government documents to significantly undermine the scientific consensus on climate change in the wake of a 2002 United Nations report that emphasized its threats. Ebell perfected the strategy of attacking the EPA as a faulty and corrupt source of knowledge. His aim, as he wrote in an email to Cooney, was “to drive a wedge between the President and those in the administration who think they are serving the President’s interests by publishing this rubbish [the UN report].”

And so, Ebell entered the Trump transition with sharpened practice in seeing this goal through. Though he was on Trump’s shortlist to chair the EPA for the next four years, Trump eventually nominated Scott Pruitt, an Oklahoma senator who describes himself as “a leading advocate against the EPA’s activist agenda.” Fuller explained that Ebell probably wouldn’t have taken the position anyway, as “he thinks that his proper role is as a critic standing outside the bureaucracy, not being a part of it.”

But Ebell has already made his mark. His appointment suggests that Trump’s “open mind” about climate change will quickly be swayed in a free market, non-interventionist direction—as will the rest of the administration’s environmental bureaucracy. Already, all mention of climate change has been removed from whitehouse.gov, replaced with Trump’s promises to reboot the coal industry and increase oil and natural gas drilling on federal lands. In his first week, Trump signed executive orders rebooting construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Keystone XL Pipeline. The administration has also ordered EPA employees to halt social media reports and press releases (including scientific studies) indefinitely, until the Trump agenda is set. Ebell told the New York Times that the new EPA’s intention was to “implement all of the president’s campaign promises—every single one.” The next steps will likely involve gutting key environmental policies shaped by Obama’s executive orders and limiting environmental groups’ influence in EPA procedures. In short: dismantle as much of the Obama administration’s activist measures on climate, as fast as possible.

Ebell is thus one of the most successful figures in his line of work—a very peculiar, yet very powerful role that is often labeled “climate change denier.” But Ebell will insist that he can’t properly be called a climate change “denier.” He does not claim to be a scientist—he presents, he says, the “informed layman’s perspective.” He will tell you in a matter-of-fact tone that he does think climate change exists and that there is human influence. But he will say that the human influence is greatly exaggerated, that the consequences won’t be all that drastic. He claims that climate change has always been a politicized issue, that liberals are using it as a fear-mongering device to weaken the public so they readily give consent to more government control. In his view, the whole movement is built on a coalition that endorses a Neo-Marxist philosophy of empowering the liberal elites to create an “alternate reality”—climate change—as justification for radical social change.

Only once he’s instilled in you a reasonable amount of doubt and distrust in these elites will he start pointing out possible flaws in the science. And he might convince you.

“I think he’s actually a credit to his philosophy major. He is brilliant at the art of argument,” Economics professor Mark Smith said. Smith didn’t teach Ebell, but he met him in DC in 2008 and brought an Environmental Policy class to CEI headquarters to speak with him.

“If you met Myron Ebell, you would like him,” Smith told me. Plain and simple. It makes sense given what his professors say. Fuller described him as a “charming conversationalist” and Cramer told me, “I liked him, a lot.”

From Smith’s perspective, Ebell is a master of subtle persuasion. Within a few minutes, one of the world’s leading climate change contrarians had a group full of students who probably hoped to dedicate their careers to fighting climate change laughing and smiling along with him. According to Smith, it went like this: first, he talked about his childhood on a cattle ranch in Oregon—affirming his connection to the land. Then he described his years at CC, telling stories about the Block Plan—relatable. Then, he talked in an abstract way about values that we all seem to have: freedom, individuality, self-control. Before anyone knew it, he was explaining why the United States absolutely should not form policies intended to stop climate change. Smith explained how he did it: “[He’s] moved 280 degrees and it’s always been by half a degree, so that you haven’t really noticed… he’s much more Oxford Debating Union than he is Donald Trump. It’s not that [climate change] is a hoax created by the Chinese.”

I watched a few clips featuring Ebell—the classics of the “Bill Nye debates the Climate Skeptic” variety. Often, though, the scientists featured are not as likeable and adept at public communications as Bill Nye. In terms of presentation, Ebell clearly outperformed nearly every scientist he was pitted against. He reasons well and smoothly pulls off sly jabs, all while appearing calm, dignified and intelligent. His opponent, however, always seemed to fulfill the worst stereotypes of scientists: an unkempt man in a cluttered office, stuttering and bumbling to explain his work, constantly on the defense.

Right after speaking with Ebell, the presumably bewildered students were bussed to the Center for American Progress, where the policymaker they spoke with ranted for five minutes about how preposterous it was that they even visited CEI. “From her perspective it was like going to talk about race relations with David Duke,” Smith said.

Ebell’s college roommate, Glenn Williams, expressed a similar scathing critique. He wrote in an email, “I was not surprised when he went off and sold his soul to the Reaganite establishment and took the job he has held up to now. Even though he constantly claims that his opponents’ positions are just silly and that he doesn’t know why he bothers answering them, he has been lucratively employed to do just that for a very long time…There was plenty of distrust of government around. He seems to have honed that distrust into a position that government interference is always bad and that corporations and private industry would always do a better job (of course, they pay better as well).”

There’s an easy formula that puts together the puzzle pieces of Ebell: conservative, climate change denier, works for a policy group that gets showered in funds from Exxon Mobil. A cynic would draw a quick conclusion: this guy’s in it for the money. I mentioned this to Susan Ashley, and she quietly shook her head.

Not Myron.

“He would’ve reached that view after thinking hard about it,” Ashley said.

Whatever his intentions, what’s clear is that he’s good at seeing them through. He has somehow found a way to make a conservative argument appear moderate, and to make a political argument appear scientific. But most interestingly, he’s found a way to make a rather nuanced argument appeal to the masses.

He has done so by striking the perfect balance between appealing to a sense of distrust of the elites and the desire for security that everyone has. He weaves a narrative that convinces people that climate science is a ploy by the left, without instilling even a hint that climate science skepticism is a ploy by the right. Climate scientists are stuck in a hole: if they admit that their dedication to the science is connected to their views that the government should act, they risk being demonized as ideologically influenced. But Myron Ebell can admit that climate change is happening and that there is some human cause, while unilaterally condemning any restrictive policy to stop it. As an outsider to science, he isn’t held to its standards of objectivity. The result is that climate scientists have struggled against Ebell and his coalition for decades to almost no avail.

Those urging action on climate change are essentially telling people that their ways of life are problematic, which often only makes them defensive and unwilling to consider the evidence. Activists’ resounding defense—the science is on our side—isn’t working. The more that liberals insist that climate science isn’t open to interrogation, the more conservatives hear this as the maniacal work of an institution that they already don’t trust, trying to establish its control over their lives. Influential conservative policy wonks like Ebell have been adept at promoting these arguments for years—and it works in arenas beyond climate change, too. Look how readily rural white Americans, feeling abandoned by establishment politics, gravitated towards a candidate who insisted that Mexicans crossing the border are rapists who are stealing their jobs. Trump capitalized on a deep-seated distrust of the establishment combined with white America’s perception that their way of life was being threatened. But while Trump is the populist face of their movement, perhaps the more powerful players are the subtle engineers who have been behind it all for years.

Yet another one of these subtle engineers is a CC grad. David Malpass, who graduated in 1976 with a major in physics, played a key role in the transition team. After CC, he went on to earn a master’s degree in Economics at the University of Denver, and launched himself into a successful career as a highly influential Wall Street economist, working for Bear Stearns until it was the first bank to collapse in the financial crisis of 2008. He now heads a consulting firm, and in May was tapped to be Trump’s economic advisor.

I couldn’t find out as much about Malpass’s CC years. He grew up in Boulder, came to CC on a full-ride Boettcher scholarship and graduated in three years. Physics professor Dick Hilt taught him in one class, but he only remembered that he earned an A—not anything peculiar or striking about his persona. Though he has since returned in 2007 to give a keynote economics lecture, he seems less connected with the college than Ebell.

Still, it’s shocking that CC has produced two Trump transition leaders—hardly anyone else in his transition team graduated from a small liberal arts college. CC wasn’t particularly conservative in the time period when Ebell and Malpass attended. And as both Ashley and Fuller pointed out, CC has produced plenty of high-profile leaders for the left, like Diana DeGette, a well-respected Colorado representative, and Ken Salazar, who was poised to lead Hillary Clinton’s transition team had she won. All of these people are part of the college’s political legacy. But the fact remains: Ebell and Malpass weren’t aberrations who somehow escaped with their diploma without thinking about anything. There’s a reality that liberal CC students who condemn Ebell have to contend with: not all of its graduates are going to be proactive about stopping climate change, or advancing equality, or any other progressive solution that most of the student body supports. That doesn’t indicate their stupidity. As Ashley said, “You can’t say that the people with whom you agree have a monopoly on intelligence or analytical power or critical acumen.”

To be true to Ashley’s maxim, you would have to not only acknowledge that Ebell is a skilled rhetorician, but consider the possibility that he is still an adept critical thinker and that his arguments are rigorously evaluated by an internal process of skepticism, not the route to a predetermined conclusion. And you’d have to hold yourself and all other evidence to the same standard. You would have to consider the possibility that the government has no responsibility to protect the Earth and that climate science is faulty.

If this sounds crazy, that’s the point.It means you’re entering the realm of internal predispositions you didn’t even know you had. You would have to admit that your own biases might be as engrained as the people with whom you disagree. Perhaps, for example, you do blindly trust scientific institutions without doing your own research. There are already plenty of people accusing you of exactly this problem. The current wave of populism has been accompanied by a rising distrust of academia, even beyond climate science. Especially since the election, even progressive commenters like the New York Times’ Nick Kristof have written pieces renouncing the disconnect between secular colleges and universities (especially private, elite ones) and the greater American reality. The rallying cry from Trump’s coalition is that we liberal college students are just as brainwashed as we think evangelical Christian creationists are, only that our ideology comes with fancier words, a higher price tag and an annoying tendency to work itself into mainstream legitimacy.

Tim Fuller, who is known to be one of CC’s relatively conservative professors, thinks the problem is not a lack of contrary opinions, but a groupthink dynamic that pretends those opinions don’t exist. I told Fuller about many students’ dismay and anger that CC produced Myron Ebell. He said, “Everything you say confirms my belief that you’ve just got the idea that if you come to CC, there’s only one right thing to think. And of course, a liberal education is supposed to be about learning to think for yourself. And that means you might end up thinking something that everybody else around you doesn’t think.”

Fuller drew an exasperated sigh, like he had just gotten something off of his chest.

“So that’s worth thinking about,” he said.

Students who are frantically concerned about the best way to fight the incoming administration might, understandably, be wary of this approach. Why question your beliefs at the exact moment when standing up for them is most important? But dismissing all other arguments—even climate change denial—as nonsense doesn’t change anything or persuade anyone that you’re right. In a time of intense political contention, you have to walk a fine line between adamantly defending your core beliefs and giving them enough interrogation that you avoid descending into mere repetition of dogma. As a college student who is intentionally taking four years to learn (even from ideas that seem wrong), you have good reason to edge towards the latter. But even if you’re a hardline activist who finds it abhorrent to question climate science, consider this: if we can learn anything from Ebell, it’s that engaging with the other side can help you fight against it. You can’t undo the effects of manipulative rhetoric without understanding it, and you can’t reach individual people without giving their perspectives some integrity. That begs a question: would you take a seminar on conservatism? And would you take it as seriously as Myron Ebell did when he studied the ideology he has since spent his life working against?

Part of the Toxic issue